Superstar R&B Artist Official Angello

Allister Amada Spoken Word Contest Winner

Winner

Lilian Langaigne contest winner

Jenson Mitchell aka Highroof Spirit Lead Spoken Word Piece

Ellington Nathan Purcell aka “Ello”

A must watch Spoken Word

PRE and POST MARCH 13, 1979 REVOLUTION

Pre-Revolutionary Grenada

Did You Know

By early 1950’s the Grenadian colonial economy was a classic example of a small scale plantation type economic system. The economy, based on small sized plantations of cocoa, nutmeg and sugar, was owned by the very small, light-skinned elite group. The peasantry eked out a living on their small plots of land or on seasonal employment offered by the export oriented plantations. With a per capita income at about $250, unemployment and underemployment caused serious hardships for the Grenadian majority.

This colonial economic system went hand in hand with a Crown Colony government in which power resided in the hands of the British Governor assisted by his civil servants. Until the granting of universal adult suffrage in 1951, the majority of Grenadian population did not participate in the political process.

Working on the plantation

Working on the plantation

Gouyave nutmeg pool

iamgrenada.com

Eric Gairy came to power on the back of strikes organized by his trade union but quickly betrayed the working class. Gairy’s title was Premier as Grenada became an Associated State in free association with Britain. In general, this new relationship meant that Grenada, led by Gairy, controlled its internal welfare, with Britain responsible for defense and external relations. In this sense, Grenada was a client of the British State, a colony built for exploitation.

By 1967, Eric Gairy had emerged as an extremely controversial figure who generated strong feelings both for and against his leadership. His appeal was based on a curious admixture of a charismatic-type personality; a skillful manipulation of religious symbols including his involvement in voodoo-type worship; and ultimately, the emergence of the “Mongoose gang.” This latter group comprised largely of thugs, roughly akin to the Tonton Macoute of Haiti, emerged during the 1967 elections and were not disbanded until the NJM coup twelve years later.

Gairy’s cavalier attitude toward leadership and administration of state affairs contributed during this period to his ultimate downfall. This administration was characterized by personal corruption, financial mismanagement, fiscal inefficiency, and the emergence of arrogant and somewhat dictatorial leadership.

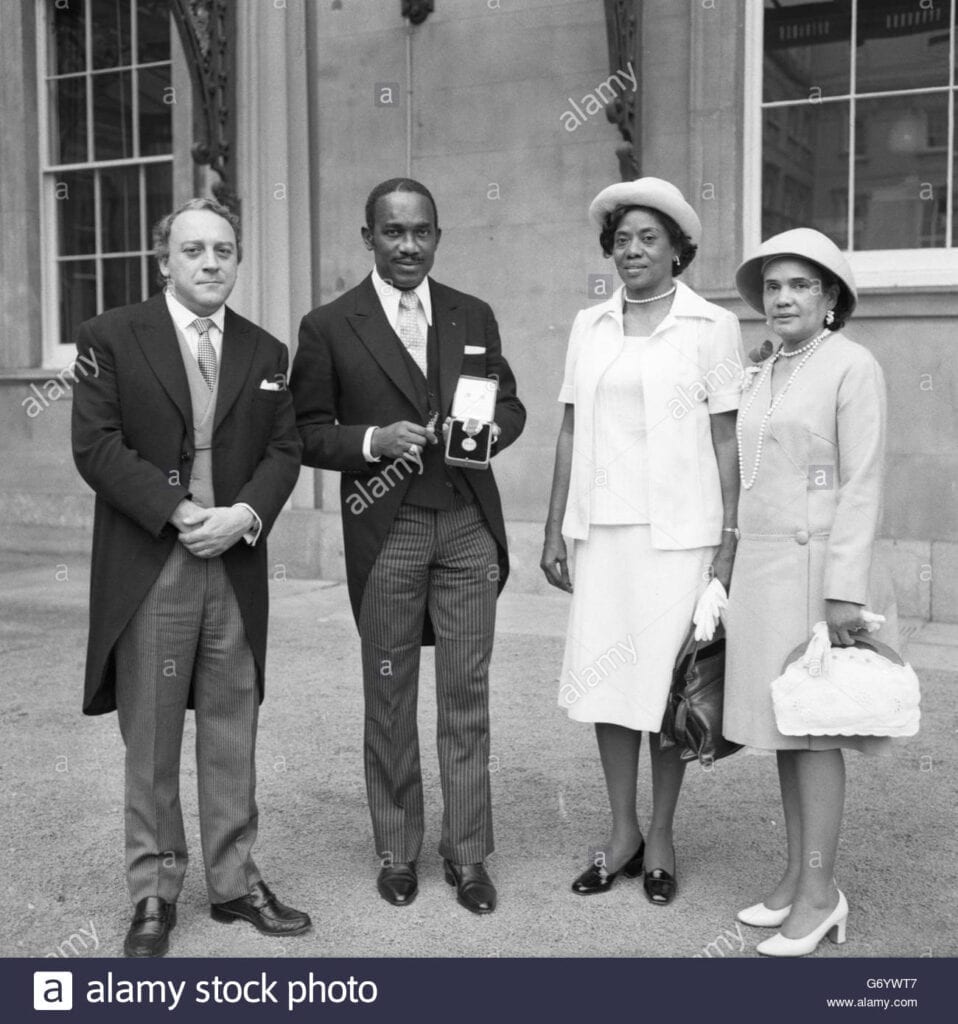

Sir Eric Matthew Gairy

Lady Cynthia Gairy

iamgrenada.com

Sir Eric Matthew Gairy

There was little discernible government planning. While the land reform program permitted the government to acquire twenty-six estates, very little of this was redistributed to the poor and landless. Moreover, the ever-present threat provided by Gairy’s Mongoose gang did not contribute to open participation in the democratic process.

Between 1974 and December 1976, Gairy’s party controlled 14 of the 15 seats in parliament. The lone opposition member was rarely in attendance. During the second phase from December 1976 until the coup in March 1979, there was a strong opposition party since the government now controlled 9 of the 15 seats. However, during both periods, the Parliament was a mere “rubber stamp for the government decisions that had already been made elsewhere.” However, because of Gairy’s decision-making style, “questions in Cabinet were not always resolved by debate and majority resolutions (since) Cabinet members merely echoed the views of the Prime Minister.”

It is also interesting to note that during the entire duration of the second independence parliament, a period of twenty-seven months, the Parliament met for a total of eighteen days even though the constitution demanded more frequent meetings. While the formal structure of democratic institutions and processes existed, decision-making over the five-year period became increasingly concentrated in the hands of Prime Minister Gairy.

This concentration persisted to such a degree that Gairy’s own personal idiosyncrasies became serious issues of policy. At the United Nations, Gairy’s Grenada made significant issues of UFOs, psychic research, and the mysteries of the Bermuda Triangle.

It was this climate of fear and intimidation of the increasingly economically depressed masses that provided the setting for the New Jewel Movement. In short, the Grenada revolution occurred because of the complete immiseration of the masses.

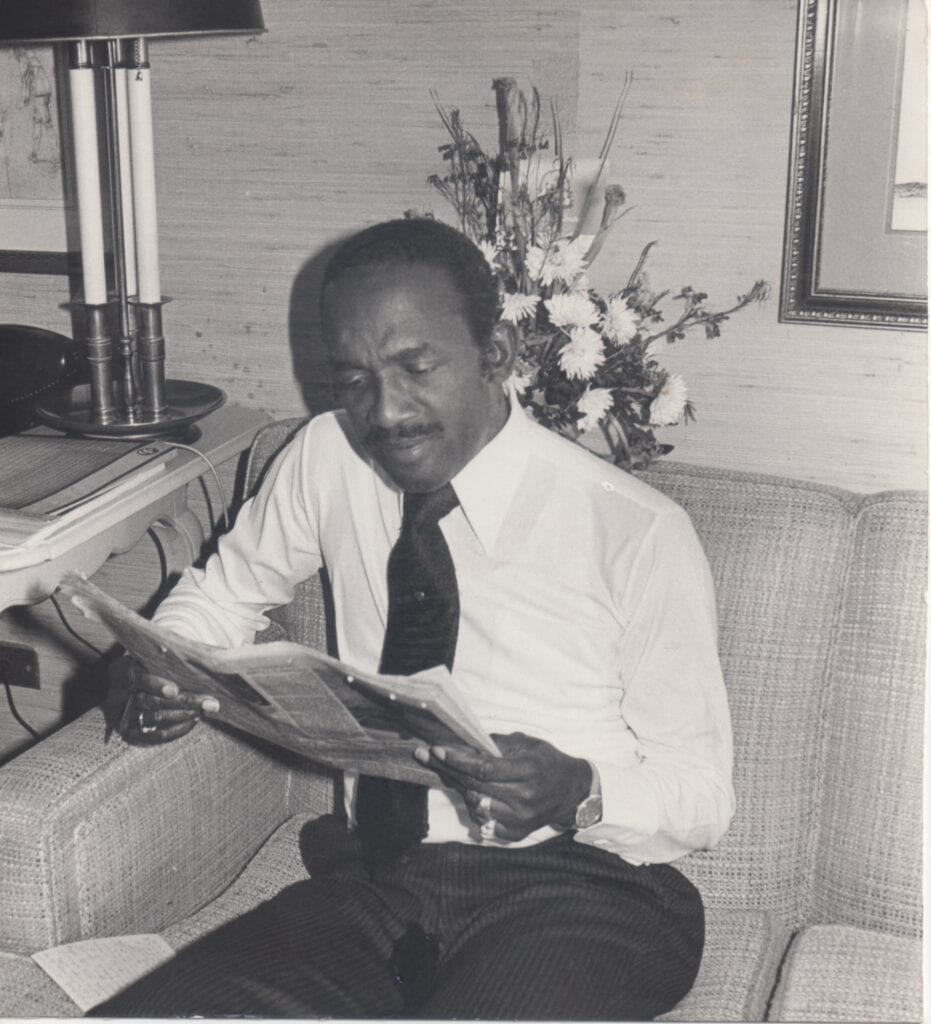

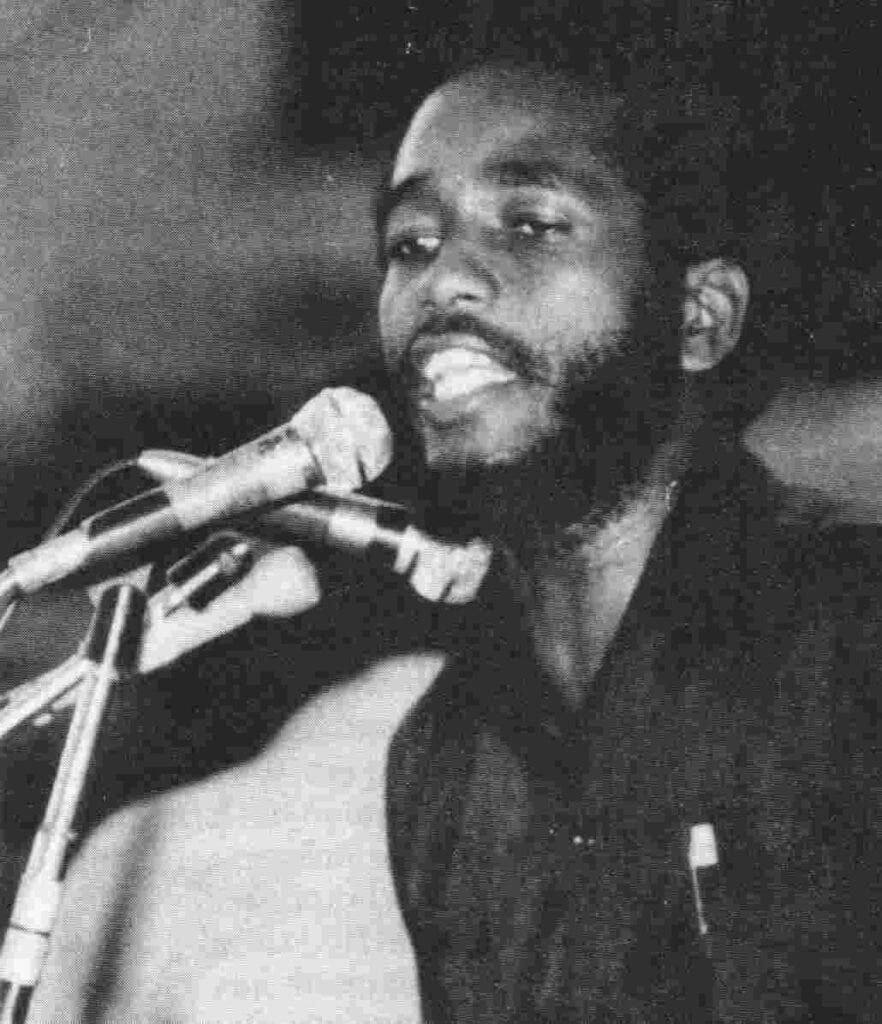

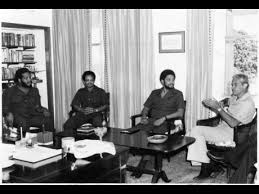

A REVOLUTIONARY AT HEART

iamgrenada.com

Charisma

iamgrenada.com

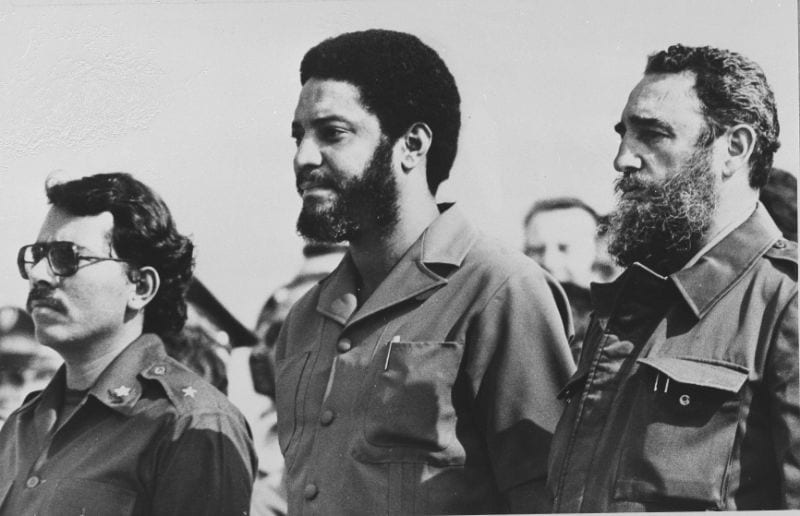

In later years he recalled being interested in politics, history and sociology at a young age. He also spoke on the interest that the Cuban Revolution of 1959 had sparked in him saying, “In fact, for us, it did not matter what we heard on the radio or read in the colonial press. For us, it comes down to the courage and legendary heroism of Fidel Castro, Che Guevara. …Nothing could overshadow this aspect of the Cuban Revolution.” Bishop’s ability to resonate with the Grenadian people has also been compared to Fidel Castro’s relationship with the Cuban people.

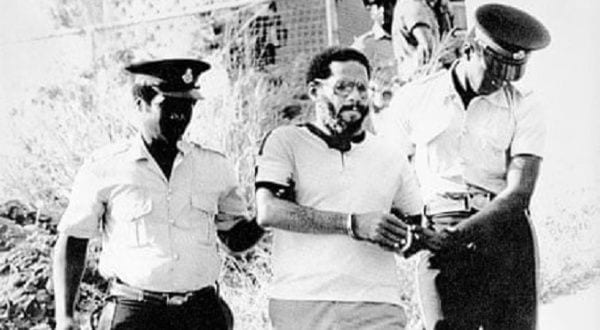

His life’s work is embedded in the history of Grenada, because of the events that followed him after the creation of the NJM. On November 18th, 1973 as Maurice Bishop and the leaders of the NJM were traveling to the east side of the island to meet with businessmen, his company was ambushed, under the command of Assistant Chief Constable Aynesent Belmar, and nine of them, including Bishop who had his jaw broken, were captured, arrested and beaten.

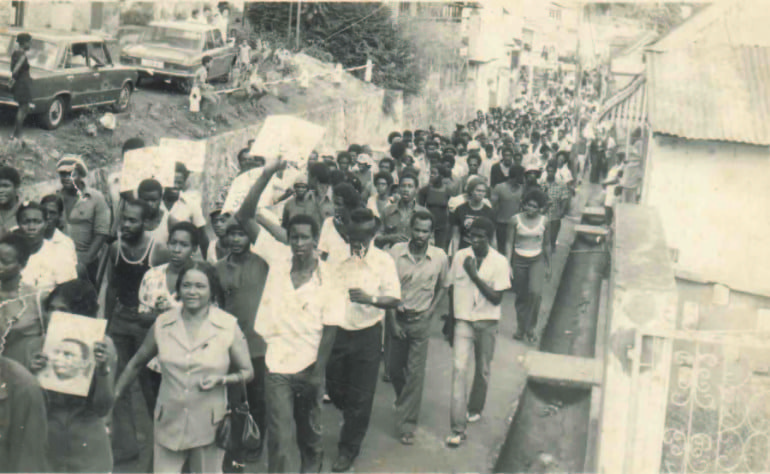

This event is now called “Bloody Sunday,” and two months after on January 21st, 1974 “Bloody Monday” came to be when Bishop joined a mass demonstration against Eric Matthew Gairy. Gairy’s supporters assaulted Bishop’s group as they tried to return to their hotel, and Rupert Bishop, Maurice’s father, was shot and killed as he tried to lead women and children away from the violence. Bishop and his team then revised their strategy to focus on the organization of party groups and cells instead of propaganda and anti-government demonstrations.

Maurice Bishop continued to practice law and spoke on Caribbean committees, meeting with other Caribbean leaders and developing his political strategy. Five years later, in 1979, Bishop’s party staged a revolution and deposed Gairy while he was in the United States. Bishop became Prime Minister, suspended the constitution and created a relationship with Cuba. Some of his core principles were workers’ rights, women’s rights and the struggle against racism and apartheid. He initiated several projects which included:

Maurice Bishop International Airport iamgrenada.com

- The international airport which is currently known as the Maurice Bishop International Airport,

- The National Women’s Organization

- The National Youth Organization

- The People’s Revolutionary Army.

- Introduction of free public health care,

- The reduction of illiteracy rate from 35% to 5%,

- The reduction of the unemployment rate from 50%to 14%.

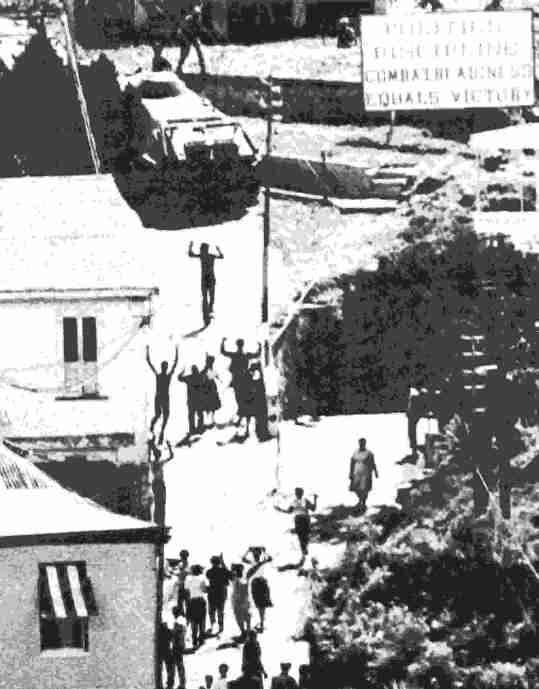

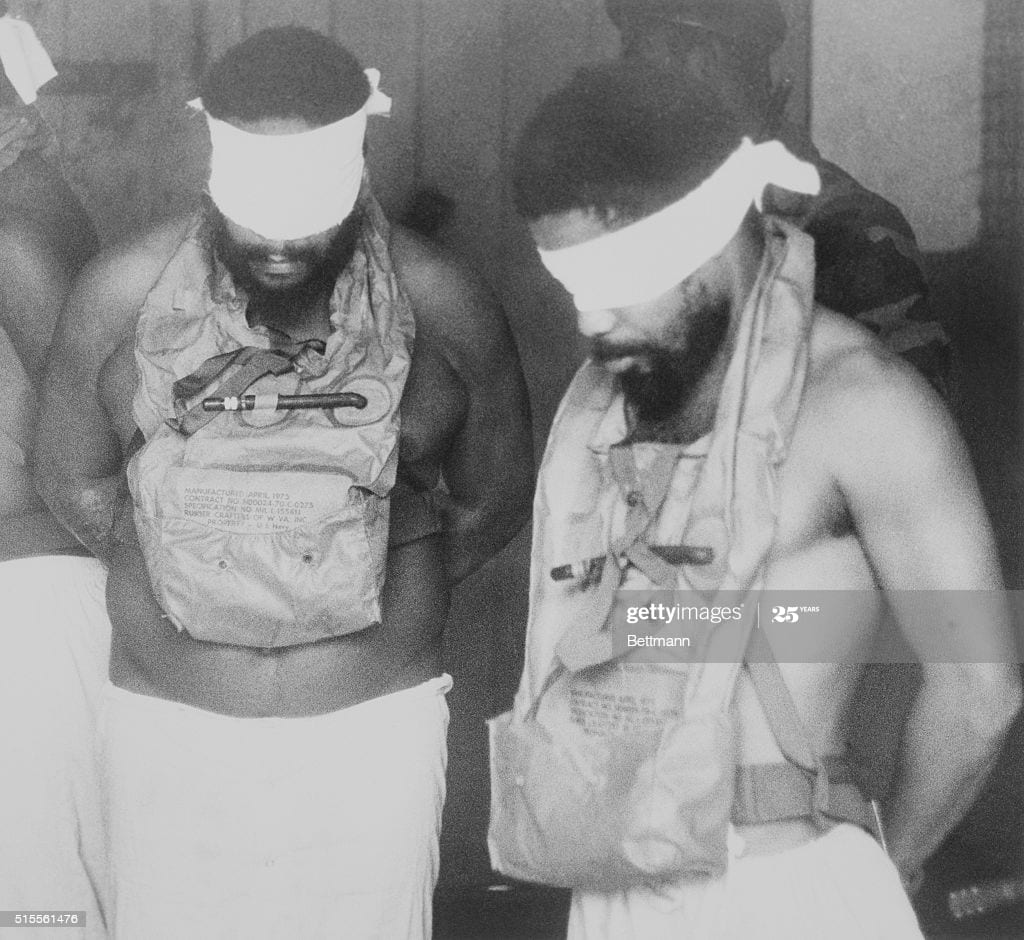

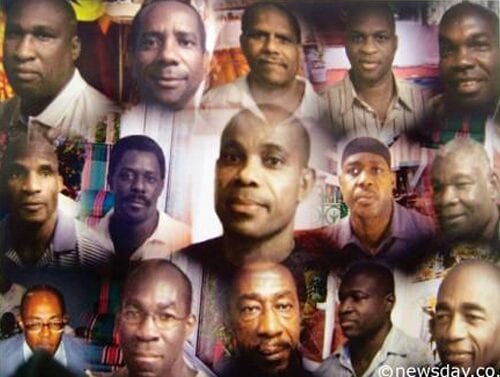

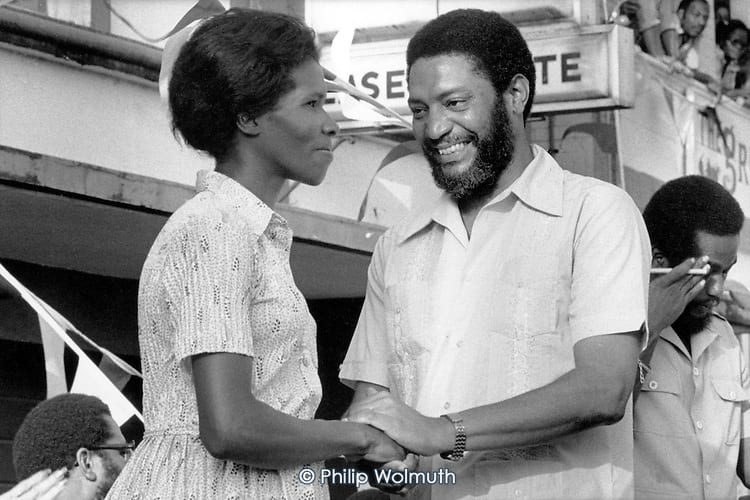

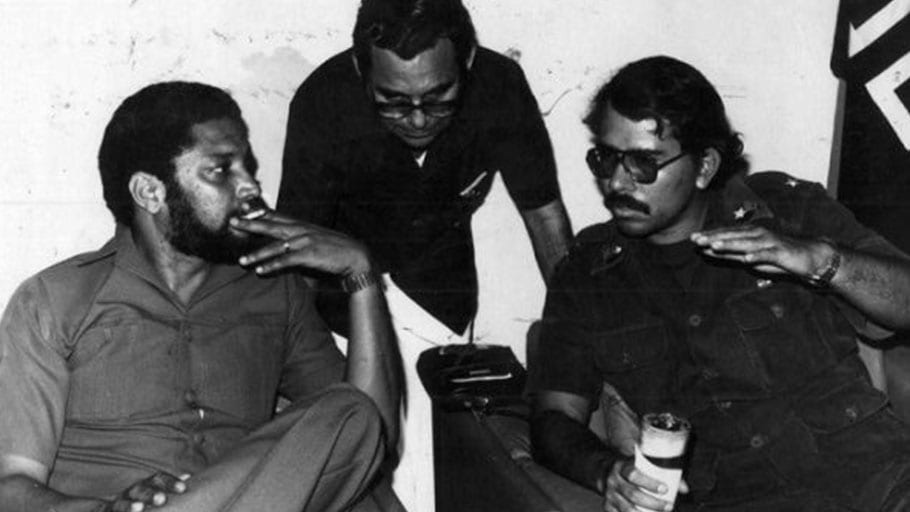

In 1983 when disputes among the party leadership occurred, Bernard Coard, the Deputy Prime Minister, had Bishop arrested and placed under house arrest. This caused mass public demonstrations across the island, and at one point the supporters were able to free him from the detention and he made his way to the army headquarters at Fort Rupert, now known as Fort George. His escape proved to be fatal as a military force was dispatched to capture Bishop and seven of his associates. The People’s Revolutionary Army firing squad executed Maurice Bishop, his longtime partner Jacqueline Creft, and six others.

iamgrenada.com

Jacqueline Creft

iamgrenada.com

Fort George, the execution of at least 24 persons in the central courtyard including Prime Minister Bishop

He left behind his ex-wife, Angela Redhead, his three children, Nadia, John and Vladimir Lenin who died in a nightclub incident in Toronto Canada. His legacy lives on in his children, the projects that he started that are currently helping the country, and even in the people who stood by him until his very last day. His revolutionary energy is still felt among many Grenadians young and old, who believe in his ideals and his vision. This Son of the Soil was a revolutionary at heart and his revolution continues as Grenadians seek change in leadership in their government.

iamgrenada.com

Maurice friend, Bernard Coard

iamgrenada.com

The Revolution Itself

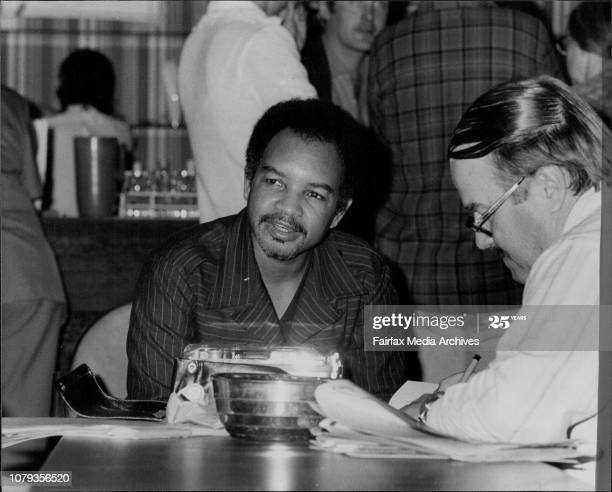

Unison Whiteman, Minister for Foreign Affairs in the People’s Revolutionary Government of Grenada, photographed at the Sydney Trades Union Clubs today. October 6, 1981. (Photo by Philip Wayne Lock/Fairfax Media via Getty Images).

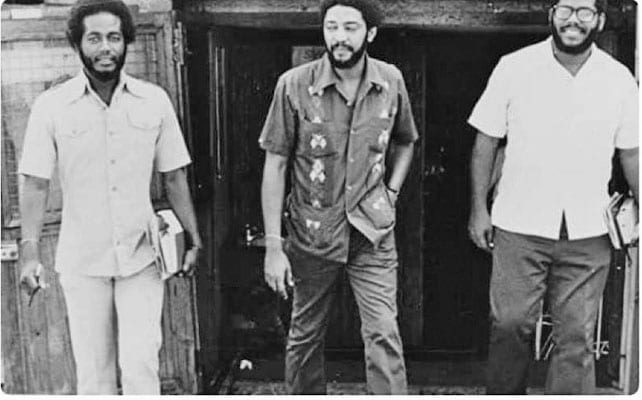

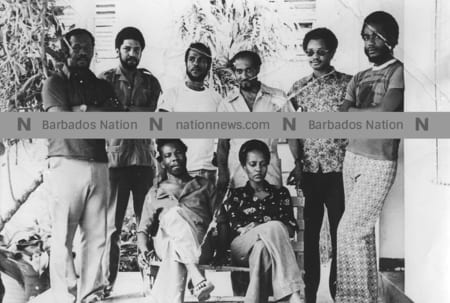

The New Jewel Movement, what eventually became known as the NJM had its beginnings with the return of Unison Whiteman, a young economist, to Grenada in 1964. Whiteman was disturbed by the conditions in Grenada’s working class. He organized a small discussion group confined largely to the strongly agricultural parish of St. David. In 1972, this group was formalized as the Joint Endeavor for Welfare, Education and Liberation aka “Jewel.”

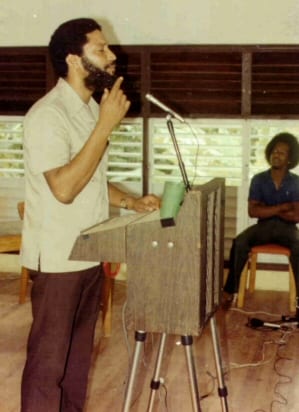

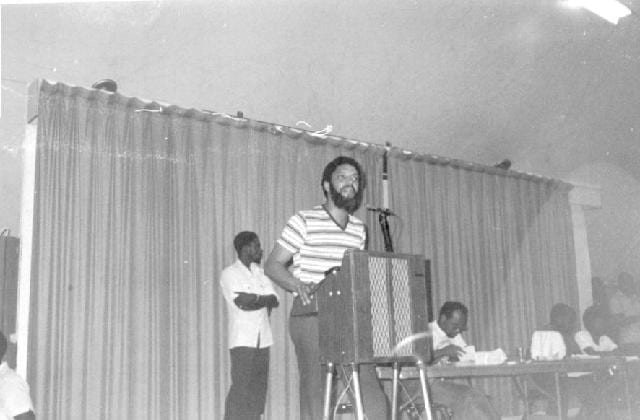

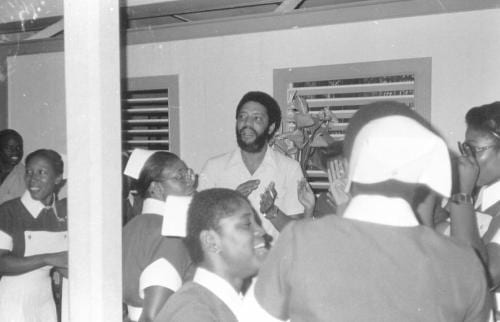

Bishop at nurses ceremony

iamgrenada.com

After legal training and involvement in the West Indian minority politics in England, Maurice Bishop the son of a middle-class St. George’s businessman returned to Grenada in 1969. He immediately became involved in domestic politics, protesting with and later successfully defending a group of nurses. The nurses took to the streets to dramatize the deplorable conditions at the government hospitals.

In 1972, at Bishop’s initiative, the Movement for the Assemblies of the People (MAP) was formed. The MAP opposed the existing Westminster model of government as non-functional to the needs of the society. The MAP instead suggested a radical alternative: the establishment of People’s Assemblies. The latter was viewed as a practical method for permitting the broader mass of the society to have more meaningful input into the state’s decision-making process. The NJM explicitly wished to expand democracy. It also wanted to improve education, schooling, healthcare, and women’s rights.

iamgrenada.com

iamgrenada.com

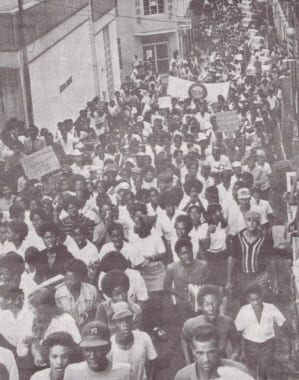

Confrontation between the NJM and Gairy’s government was swift and, in most cases, violent. In late 1973, when the NJM was engaged in a brief alliance with the GNP while both organized a series of strikes, Gairy responded with state force. Gairy invoked physical abuse of the opposition, the jailing of its leadership, and eventually, the killing of several NJM sympathizers. The events of “Bloody Sunday” became a foremost example of state violence against the opposition; and eventually, they became the turning point of opposition against Gairy. The revolution gained mass popular support, even among the middle class who had formerly allied themselves with Gairy. This was the climate in which the revolution succeeded.

It should be noted that, although there were violent confrontations in the lead-up to the revolution, the coup in which the NJM took power was bloodless. This deals a decisive blow to the idea that revolutions are inherently violent. Although there must always be some bloodshed, the idea that a revolution involves indiscriminate murder and war is false. The Grenada Revolution proves this to be the case.

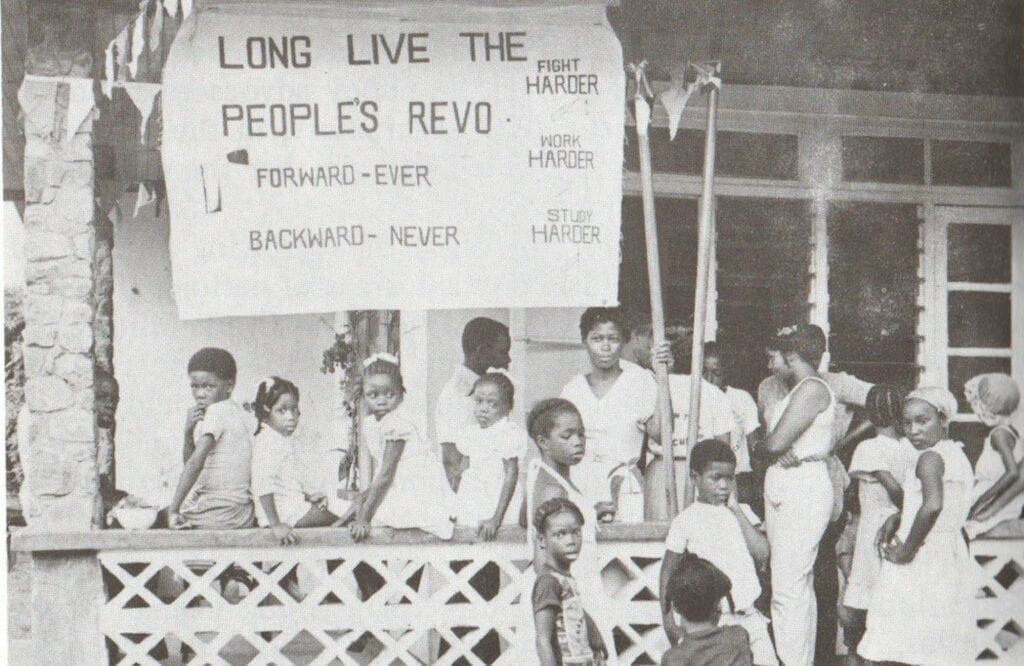

The Achievements of the Revolution

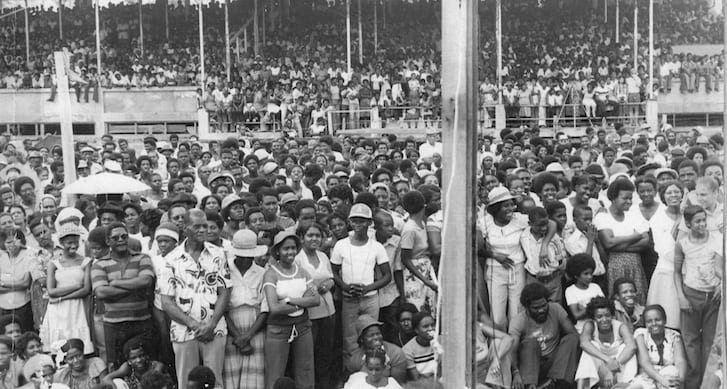

iamgrenada.com

The New Jewel Movement quickly got down to the serious task of improving the lives of Grenada’s long-suffering people. As Bishop said in his first broadcast on Radio Free Grenada after the capture of power on March 13, 1979, “This revolution is for work, for food, for decent housing and health services, and for a bright future for our children.”

Pre-revolutionary Grenada suffered with unemployment levels upward of 50%. Through the development of cooperatives, the expansion of the industrial base, the diversification of agriculture, the expansion of the tourist industry, and the creation of massive public work programs. Unemployment dropped to 14% and the percentage of food imports dropped from over 40% to 28% “at a time when market prices for agricultural products were collapsing worldwide.”

Paulo Freire was invited to design and lead the implementation of a literacy program, which all but eliminated illiteracy (the literacy rate increased from 85% to 98%). The leaders of the revolution realized that an educational system must be established that broke away from the British colonial tradition and the inferiority complex that it sought to instill in its ‘subjects’. As Bishop elaborated, “The colonial masters recognized very early on that if you get a subject people to think like they, to forget their own history and their own culture, to develop a system of education that is going to have relevance to our outward needs and be almost entirely irrelevant to our internal needs, then they have already won the job of keeping us in perpetual domination and exploitation. Our educational process, therefore, was used mainly as a tool of the ruling elite.”

Chris Searle observed an intense, widespread desire and demand for learning:

“One of the first overwhelming truths and discoveries of the Revolution was that education was everywhere, it was irrepressible! It came at once from every side and at every moment. The dammed-up flood of four centuries of the people’s urge to know, to understand, to learn, to connect, to criticize, to express themselves, was unstoppable. At meetings, at rallies, at panel discussions, through songs, poems, plays and calypso, the message poured down upon the revolutionary leaders: Teach us, we want to know! Young and old, farmer and urban worker, fisherman and the woman cracking nutmegs, seamstresses and road-workers, all clamored for more education, giving the cue for the slogan: Education is a must – from the cradle to the grave.”

By 1983, 37% of the national budget went to education and health. School fees were abolished; schools were repaired. “Free books, school uniforms and hot lunches were provided for the first time for the poor. Health care was made free and the number of doctors and dentists doubled.”

For the first time, Grenadians had a very real say as to how public funds were allocated. They chose via a People’s Budget that preempted the celebrated Porto Alegre participatory budget by more than a decade. Meanwhile, the economic growth rate averaged 10% during the years of the revolution. A World Bank memorandum on the Grenadian economy in 1982 stated: “The government which came to power in March 1979 inherited a deteriorating economy, and is now addressing the task of rehabilitation and of laying better foundations… Government objectives are centered on the critical development issues and touch on the country’s most promising development areas.” The World Bank is an institution whose sole goal is to perpetuate capitalism, so it is unlikely that it would admit such a thing unless it was accurate.

Regarding agriculture, Searle writes that “there was increased enthusiasm to work on the land. The old pattern of the plantocratic estate, the hierarchical control of the expatriate landlord or the man in the ‘great house’ and the living death of laborious daily-paid work on land which was not theirs – all this was changing. The growth in cooperatives on the land and the collective stake in production and profit had brought many young people back to the land, and three farm training schools had been established to give these young farmers some basic expertise in agriculture and cooperative management techniques.”

The revolution was strongly focused on women’s empowerment and participation. The first decree of the revolution was to outlaw sexual victimization, and women’s unions constituted a large part of the grassroots democracy discussed below.

The changes in society were reflected by a massively invigorated national culture, expressed through calypso, poetry, dance and drama. “The shyness and reticence that characterized many of the Grenadian people before the Revolution, the self-consciousness of being a ‘small island’, second-rate or unnoticed was replaced by an explosion of national self-assertion through the revolutionary culture. More Grenadians were writing poetry and performing calypso than ever before and receiving publication and air-play too.”

One of the most remarkable accomplishments of the revolution was the construction of an international airport, the first airport to be built by a post-colonial Caribbean state, built by the Grenadian people themselves. In an impressive show of international solidarity, Cuba, Angola, and Bolivia provided money and labor for the construction of what would come to be known as the Bishop International Airport.

Revolutionary Grenada came under criticism from many angles, most salient from dissenters who accused Bishop for silencing his critics and for not holding parliamentary elections. Particularly since Bishop’s first broadcast after the seizure of power the promise of the restoration of “all democratic freedoms, including freedom of elections.” This lack of elections and he silencing his critics were constantly used by the US and its regional proxies to besmirch the New Jewel government, and there were plenty of people even those broadly sympathetic to the revolution who felt that the whole experience was tainted through lack of democracy.

iamgrenada.com

iamgrenada.com

Why weren’t elections held? After all, there was never any doubt that the NJM would comfortably win at the polls. Given that Bishop promised elections in the first broadcast, there is no reason to assume that he refused to hold elections because they would have threatened his power. On the contrary, he initially argued in favor of them. This should lead us to conclude that specific material conditions prevented the NJM from holding elections after the revolution.

Bishop discussed this issue in an interview with New Internationalist in 1980:

“We don’t believe that a parliamentary system is the most relevant in our situation. After all, we took power outside the ballot-box and we are trying to build our Revolution on the basis of a new form of democracy: grassroots and democratic, creating mechanisms and institutions which really have relevance to the people, If we succeed it will bring in question this whole parliamentary approach to democracy which we regard as having failed in the region. We believe that elections could be important, but for us the question is one of timing. We don’t regard it now as a priority. We would much rather see elections come when the economy is more stable, when the Revolution is more consolidated. When more people have in fact had benefits brought to them. When more people are literate and able to understand what the meaning of a vote really is and what role they should have in building a genuine participatory democracy.”

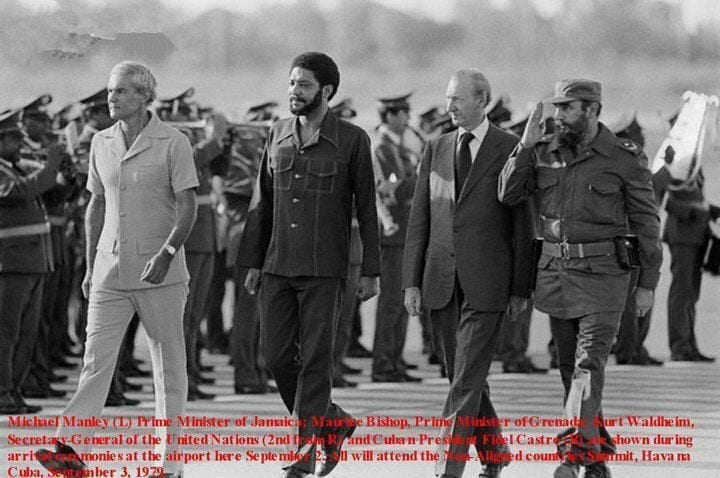

Speaking at an event to mark the first anniversary of the revolution, an event at which the guests included Daniel Ortega and Michael Manley. Bishop highlighted some of the obvious flaws of the Westminster system:

“There are those (some of them our friends) who believe that you cannot have a democracy unless there is a situation where every five years, and for five seconds in those five years, a people are allowed to put an ‘X’ next to some candidate’s name, and for those five seconds in those five years they become democrats, and for the remainder of the time, four years and 364 days, they return to being non-people without the right to say anything to their government, without any right to be involved in running their country.”

In place of a such a pseudo-democracy, there was instead a system of grassroots democracy that, by any reasonable standard, must be considered far more democratic than the pretend democracy in place in Britain and the US. Organs of power sprung up everywhere, and nearly everyone was involved in some level of organization and decision-making: The Zonal Councils, the Workers’ Parish Councils, the Farmer Councils, the Youth Movement or the Women’s Movement, and many more which met at least once a month. Free facilities were made available for all such meetings, and they were often attended by senior government figures. These government figures would have to answer directly to the people.

iamgrenada.com

In 1981, the People’s Revolutionary Government established a Ministry of National Mobilization, headed up by senior NJM leader Selwyn Strachan. This was a whole government ministry dedicated to devising means of continually spreading and improving popular participation in the running of the country and ensuring maximum levels of accountability for those in positions of power.

Searle points out that the army was expected to be at the service of the people and was deeply involved in helping to carry out decisions made by the organs of popular power. He states: “The army was involved and was extremely popular. if repairs were needed or houses had to be built, soldiers would be there.” In Grenada, the Army was built to serve the people. This is quite different from the army in a typical bourgeois pseudo-democracy, which lords above the people rather than moving among them.

True democracy is about strengthening the ties between the state and the people. This tie shows that socialist states, while repressive in some limited senses, are substantially more democratic than capitalist ones. Socialism (as well as democracy) gives the masses power. Revolutionary Grenada was a brilliant example of that power.

Interestingly, after Sir Eric was removed from office on March 13, 1979, the new rulers recognized independence as a significant milestone, though it was not celebrated with any public fanfare. It was in the post-1983 period, in the aftermath of the fall of the Revolution, that the celebration of independence took on a new tone and began moving to a new level of national pride.

Footnote:

The Mongoose Gang was a private army of militia which operated from 1967 to 1979 under the control of Eric Gairy. Mongoose Gang members were called Special Reserve Police (S.R.P.) or Volunteer Constables. Most notable were gang leader Mosylin, Heads and Willie. A news report from 1974 confirms that the “Mongoose squad” sometimes carried rifles, but generally carried “thick pieces of wood”. Mongoose Gang members also tended not to dress in any distinctive way. The Mongoose Gang was responsible for silencing critics, breaking up demonstrations and murdering opponents of the Gairy regime, including the father of Maurice Bishop.

The name ‘Mongoose Gang’ originated in the 1950s, when the local health officials sought to eliminate the mongoose as a pest, and paid people who brought in mongoose tails as proof of killing the animals. The men who were employed in such work became known as the ‘mongoose-gang’. Later, the name shifted to refer to gangs of political thugs on Grenada. In fact, it was Gairy himself who got jobs for a number of men and women on the mongoose eradication project in the 1950s when he was a representative of the Colony of Grenada’s Legislative Council. For Gairy’s part, in a 1984 interview with New York magazine, he denied employing thugs or any kind of secret police.

5 Comments

Upcoming Posts

Dave Chappelle Grenadian Roots

Shervone Neckles

Grand Etang Lake

Our history is colorful. It’s ashamed that this experiment was aborted. We all were very hopeful. It was an awesome experience.

I bought a copy of Coard’s book, How it really happened. In his book, he tries to mitigate his role but he’s just as guilty as the others. This traitor should be muzzled.

Man I missed you all. Hoping y’all here to stay this time around. I look forward to your articles.

Someone referred to the Revolution as an experiment which I thought was a different perspective and interesting too. These guys had good timing. We were tired of Gairyism. We were riped for a change. Timing is everything. They were like movie stars, our celebrities. It failed because of greed. Yes there was outside interference but it was allowed to infiltrate and influence the perpetrators.

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here to that Topic: iamgrenada.com/the-bishop-factor/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: iamgrenada.com/the-bishop-factor/ […]