Superstar R&B Artist Official Angello

Allister Amada Spoken Word Contest Winner

Winner

Lilian Langaigne contest winner

Jenson Mitchell aka Highroof Spirit Lead Spoken Word Piece

Ellington Nathan Purcell aka “Ello”

A must watch Spoken Word

THE CARIBBEAN

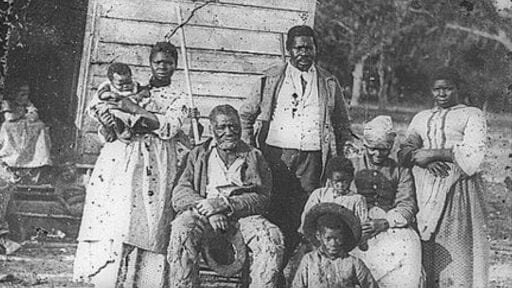

The Caribbean is composed of people from all over the world including those taken there by force and those who migrated freely.

Caribs lived in the Caribbean for thousands of years. There were many communities of people we now know as Caribs, including Galibi and various Arawakan speakers such as the Kalinago. Beginning in the 16th century, many were killed or expelled from the islands by European forces. They asserted their identity by fighting for land and political rights. One example is Brigands’ War, also known as the Second Carib War (1794 -1798).

Merchants and plantation owners moved into the region. Indentured servants, political dissidents and others from the British Isles provided the first plantation labor.

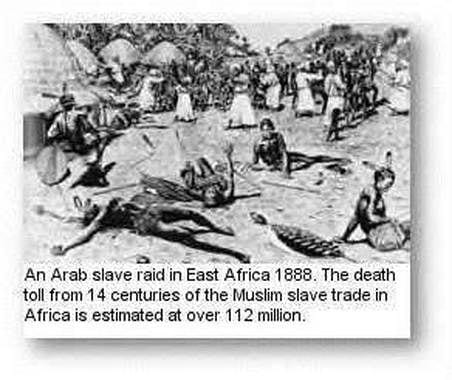

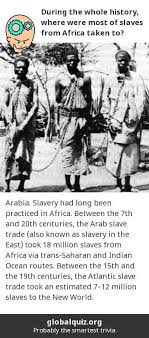

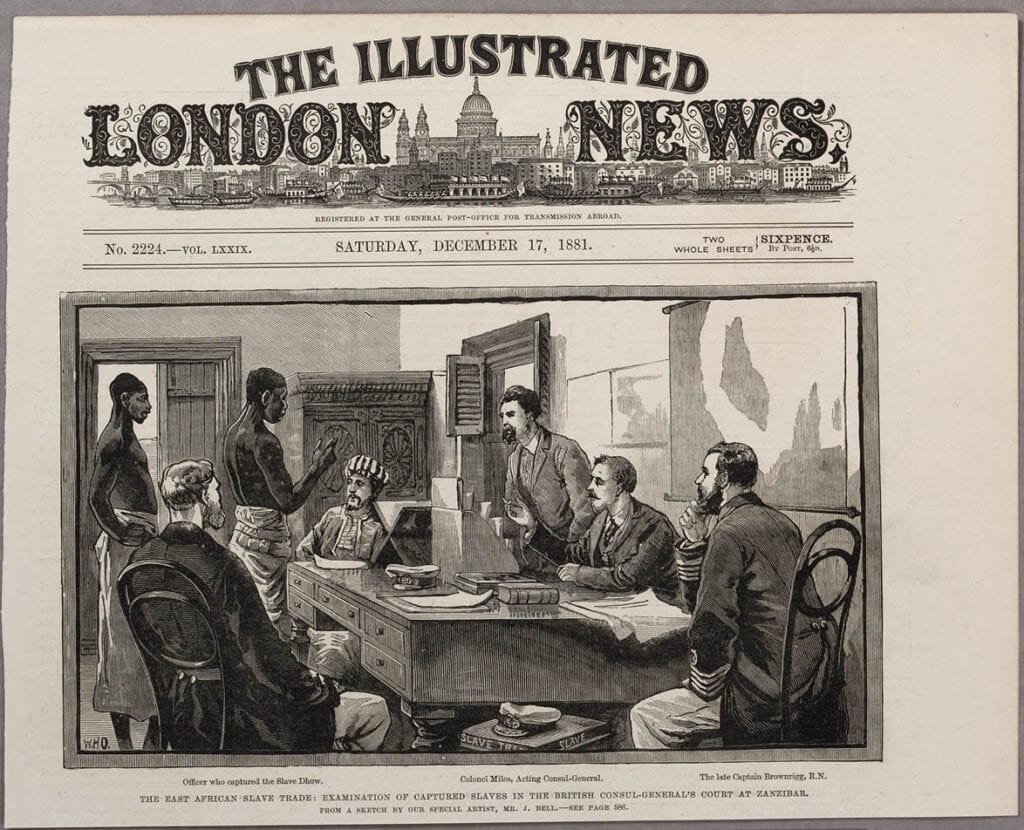

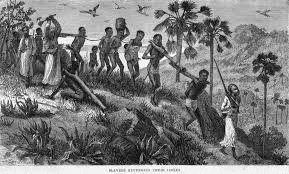

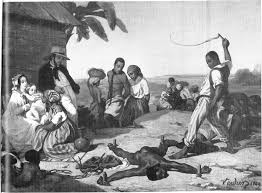

Arabs slave trade

Arabs practicing slavery in Africa

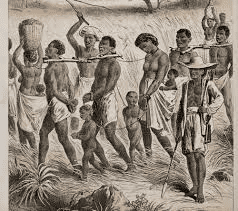

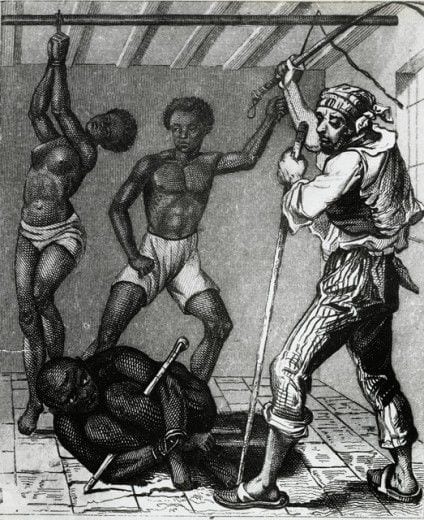

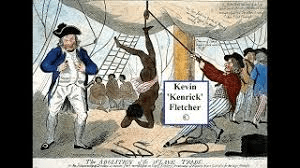

The British Government and Slavery

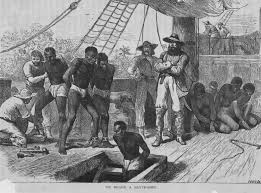

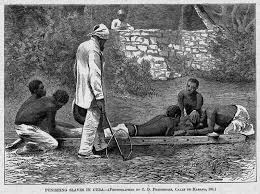

Slaves last stop before leaving Nigeria

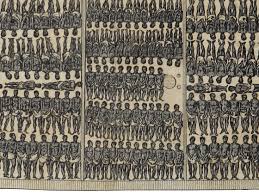

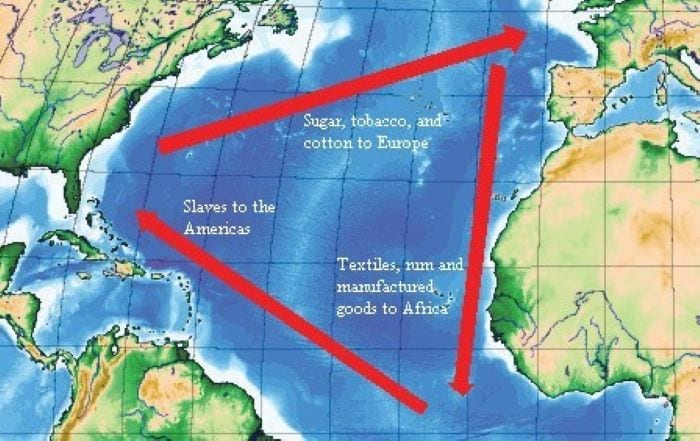

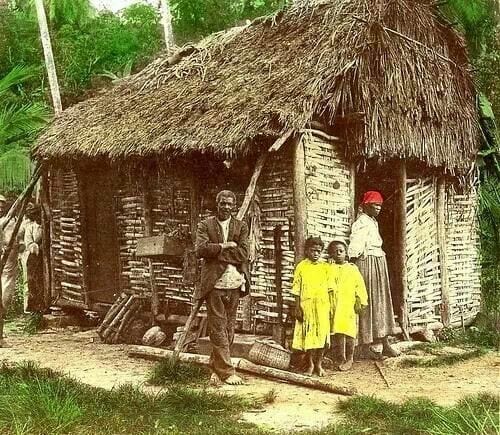

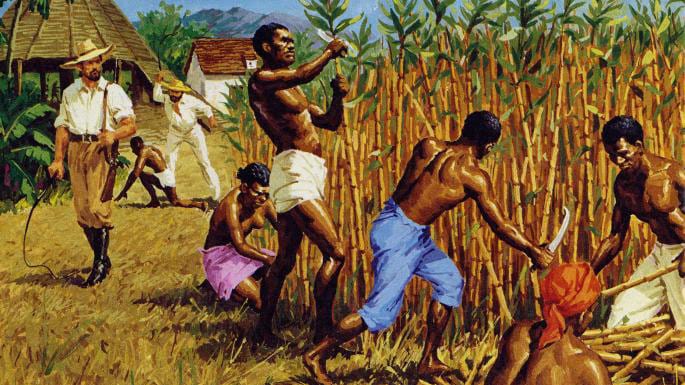

The biggest migration to the Caribbean was a forced migration of enslaved people from Africa through the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Many of the merchants who settled in the Caribbean during the 17th and 18th centuries were involved in slave trading. The early Caribbean was also a center for piracy.

In the late 18th century, Britain moved soldiers and sailors to the Caribbean to defend against invasion by competing European powers and guard against anti-slavery revolutions and protests. Former enslaved people came from Canada and joined the West Indian Regiment to fight the competing forces.

Indentured labor from India and China started in the 19th century. They migrated to the Caribbean to work on plantations in places such as Jamaica, Trinidad and British Guiana. So-called ‘Liberated Africans’ were also indentured during this time.

Many people also migrated from the Caribbean and people convicted of crimes were sometimes transported to Australia and England. Also, Bermuda had a convict establishment for British (including Irish) convicts.

SLAVERY IN GRENADA

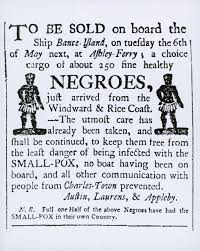

Between 1662 and 1807 Britain shipped 3.1 million Africans across the Atlantic Ocean in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Africans were forcibly brought to British owned colonies in the Caribbean and sold as slaves to work on plantations. Those engaged in the trade were driven by the huge financial gain to be made, both in the Caribbean and at home in Britain.

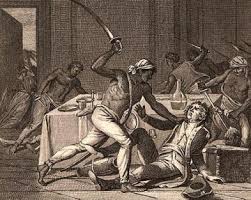

Enslaved people constantly rebelled against slavery right up until emancipation in 1834. Most spectacular were the slave revolts during the 18th and 19th centuries, including: Tacky’s rebellion in 1760s in Jamaica, the Haitian Revolution in 1789, Fedon’s Rebellion in 1790s in Grenada, the 1816 Barbados slave revolt led by Bussa, and the major 1831 slave revolt in Jamaica led by Sam Sharpe. Also, voices of dissent began emerging in Britain, highlighting the poor conditions of enslaved people. Whilst the Abolition movement was growing, so was the opposition by those with financial interests in the Caribbean.

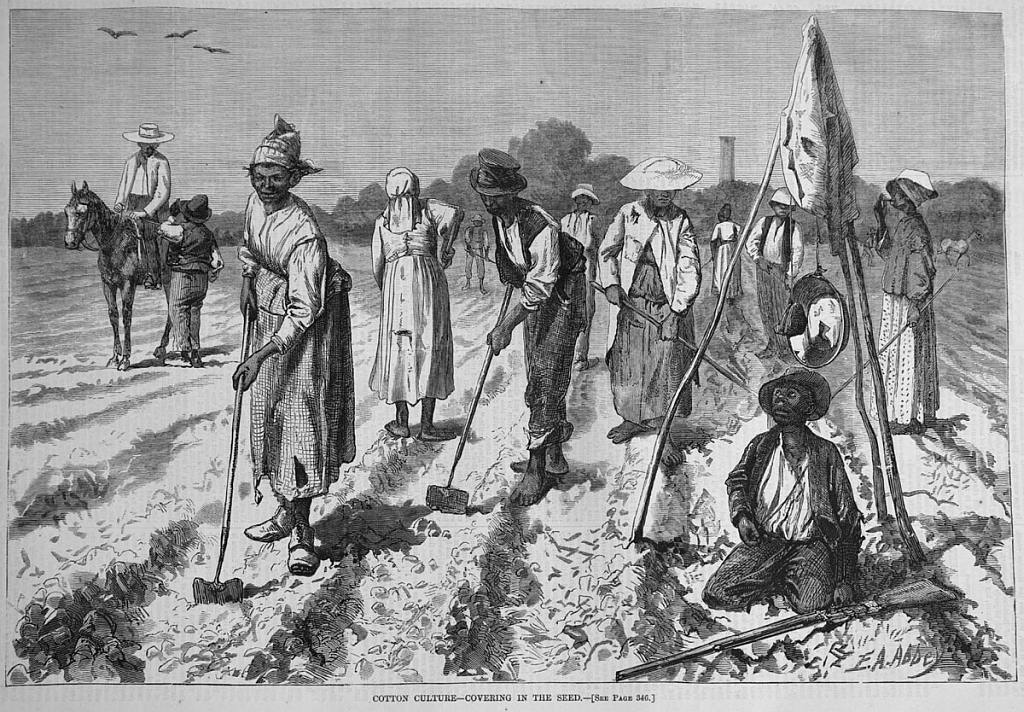

A major rethinking of Caribbean historical discourse on slavery has placed the role of women at center stage. Groundbreaking work has been done by Lucille Mair, Hilary Beckles, Barbara Bush, and Barry Higman, among others. These historians have shown that slave women provided the dominant agricultural labor input on British Caribbean sugar plantations from at least the end of the eighteenth century. Furthermore, there was an increased dependence upon women for reproduction of plantation labor. This dual role placed the women at the center of planter strategies designed to ensure the survival of the slave system. The slave woman was also shown as a rebel. These studies however have been predominantly on the larger islands (Jamaica, Trinidad, and Barbados). This article seeks to answer the following questions:

- Did Grenadian slave women provide the dominant agricultural labor on the sugar cane plantation?

- How successful were the planters’ attempts at natural increase?

- What forms of resistance did slave women take against slavery?

The Ratio

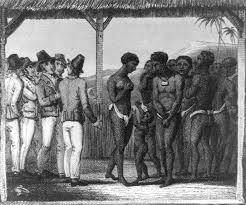

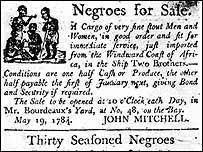

From the onset of the slave trade to the Caribbean, female slaves were imported in smaller numbers than male slaves. This was so for Grenada in particular and the other colonies in general. (British, French and Dutch Colonies). By 1788 slave owners in Grenada estimated the proportion of male to female slaves at 5:3. They further noted that in imports from Africa, the number of males in “a well assorted cargo” usually exceeded that of females in proportion of two to one. In a list of slaves sold to Grenada after its restoration to the British between 1784 and 1788, 8216 male slaves and 5346 female slaves were bought. The planters also paid lower prices for female than male slaves. In response to an inquiry by agents for West Indian Affairs in 1788, the spokesman for the Grenadian plantocracy was noted as saying:

“Putting tradesmen and drivers out of the question and speaking only of able healthy young field slaves, the average value of a creole man of that description may be stated at present in Grenada at sixty pounds sterling and that of a creole woman at fifty pounds sterling.”

While it could be argued that the price difference was small, there were fewer African females imported than males. Studies available on the relationship between mortality and sex in the Atlantic slave trade make it evident that mortality rates of females were the same as or even less than those of males of the same age group.

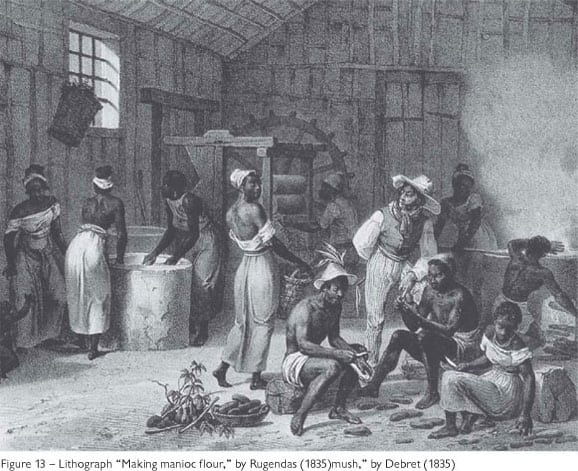

In Grenada female predominance in the field was seen after 1800. For example, in 1789 on the Lataste estate in the Parish of St. Patrick, there was still a male majority in the field: 48 men and 43 women. However, by 1804, inventories for Lower and Upper Pearls Estates in the Parish of St. Andrew show a significant number of women in the fields. On the Lower Pearls Estate of the 90 field slaves, 64 were women and 26 were men. Of the 11 domestics, 6 were men and 5 were women. All the élite jobs were taken by the men. There were 5 carpenters, 10 coopers, 2 blacksmiths, 3 masons, 3 boilers, 3 drivers, 20 carters and mule boys and 5 watchmen. On the Upper Pearls Estate of the 89 field slaves, 64 were women and 25 were men. Again the men dominated the élite jobs. By 1811, on the La Taste Estate, of the 62 field workers, 38 were women and 24 were men. Here again the men dominated the élite jobs. There was a 26-year-old female stock keeper named Zabeth and a 60-year-old stock keeper named Adelaine. Other skilled women included the 50-year-old hospital nurse, Jenny and the 38-year-old washerwoman, Mary Catherine. Charlott, a 50-year-old dry nurse, was defined as weakly and 25-year-old Peggy was a domestic.

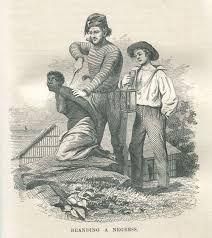

Slave women were expected to work just as hard as men and were punished just as severely. In the eyes of the master the female slave was equal to the male, as long as her strength was the same as his. Slave women in the first and second gangs did land clearing, planting, hoeing, weeding, cutting of canes, and carrying canes to the mills. At crop time, October to March, slaves worked from sunrise to sunset. They also did extended night work. Enough cane had to be cut before sunset to keep the mills running through the night. Higman estimated that the typical day worked by field slaves was 12 hours in Jamaica and ten hours in the Eastern Caribbean. The field slaves performed the hardest labor and worked the longest hours. Pregnant women were not generally treated differently in the severity of the work regime, nor in the punishments meted out for the slightest offense. Pregnant women were frequently exposed to punishment, and in such a case, a hole would be dug in the ground for the women’s belly for the purpose of preventing injury to the child. The flogging of women was abolished in 1825 by the British Government. However, Grenadian planters bitterly protested the prohibition of this measure of torture against women. They noted:

The females compose the most numerous and effective part of the field gangs of the estate; from the indulgences already extended to them they have shown themselves to be the most turbulent description of the slaves, and would become perfectly unmanageable if they knew that this description of correction was abolished by law. It is therefore absolutely necessary (for the present) that it should be held in terror over them. If suddenly prohibited it is impossible to say what might be the consequences.

After considerable resistance, the Legislative Council grudgingly passed the Act.

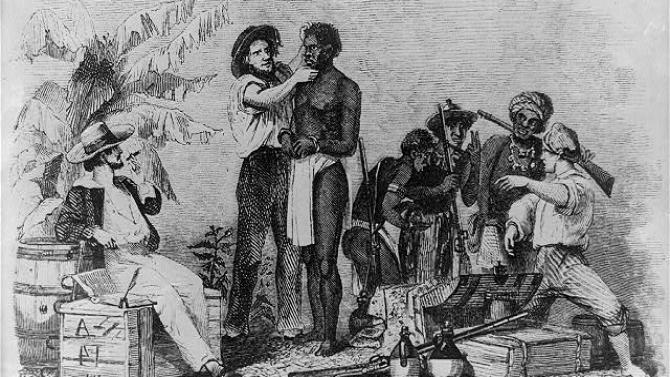

Sexual Exploitation

Female domestics were perhaps more vulnerable to physical punishment due to their close proximity to their masters. In their positions as domestics, both women and men fell easy victims to the whims and caprices of the master and his family. In this sense their jobs, while considered élite, had a major drawback. Also, it has been argued that, while both field and house slaves were subjected to sexual exploitation, the domestics were more susceptible due to their employment in the environs of the great house. Some authors placed both domestics and field slaves on an even keel in this respect. It has been argued that the female field slave was seen as the most socially inferior of all the slaves. As such, she was seen as available for sexual exploitation by her master and all the white men on the plantation. Due to their degraded condition as laborers, and the deprived material state of their existence, white men and relatively privileged slave men sought to extend their exploitation from the production to the social sphere.

Population Control

As the threats to end the slave trade became apparent, West Indian planters sought to conserve the slave population they already had and to enhance it through reproduction. The attitude of the West Indian plantocracy changed from the premise “better to buy than to breed”, to the encouragement of natural increase in the colonies. In evidence given by John Terry, an overseer and manager in Grenada between 1776 and 1790, he noted that he had never received instructions to pay particular attention to pregnant woman or their children.’ His employers, he further noted, were of the opinion that suckling children should die for they lost a great deal of the mother’s work during the infancy of the child. The slave woman’s role therefore was to make sugar rather than reproduce. Grenada however fell in line with a number of other colonies to appease, as it were, and cajole slave women into having more children.

The 1797 Act17 provided that mothers of six living children be exempted from all field labor. A hospital was to be established in proportion to the number of slaves on the estate, with a hospital book kept with names of slaves and the nature of complaints by the surgeon. Also, the planters were required to give an account of births and deaths of the slaves and causes of death. The owner of Lataste Estate in the early 1800s expressed by letter his concern with the ‘very little increase by birth’ on his estate. He claimed that the slave women were ‘very averse from childbearing and will frequently use their endeavors to procure abortion.’ He therefore advised that ‘fair encouragement’ be rendered to them to make ‘their labor very easy during the time as any great exertion would be very inconvenient to them. By 1810 measures were implemented to ‘put a stop to the practice of picking grass for the mules and cattle by the Negroes after leaving the field in the evening. This not only lessened their labor in some degree but put it in their power to be in their houses before the sunset.

Also, women were to be excused from work after delivery, and an addition was to be made to the allowance of flour for infants. For “further increasing the breeding of women”, the annual allocation of pieces of loose linen and cotton handkerchiefs was increased, and the former might be made into baby clothes. The owner went on to mention that there was evidence of natural increase in the Leewards, probably due to their practice of stopping work at crop time from 9 p.m. to 3 a.m. However, such a practice was not in his view, practical for Grenada. By 1826, Lataste was able to boast of one female slave who did bear five children.

Slaves Value

In the wake of the abolition of the slave trade the value of slaves increased. In the late 18th and early 19th century, the value of female slaves was almost on par with that of male slaves. This of course depended on the similarity of their age and skills. For example, in the accounts of the Duquesne Estate in the Parish of St. Mark for 1803-1805, there was the sale of a little “negro girl” for 100 sterling. On Bellevue Estate at St. George in 1806, when the estate was appraised, a female slave named Monique was valued at as much as 170 sterling. On the Pearls Estate in 1802, the value of male and female slaves was similar. For example, a 48 year old mill cooper named Charles was valued at 180 sterling, Rose, a 17 year old female slave, at 170 sterling. Young female slaves were valued at as much as 140 sterling, like 10 year old Mary Louise. 12 year old Paul was valued at the same price. Even older female slaves, like Faudenie at age 50, who might have fit into the category of superannuated, were valued at 150 sterling.

The ensuing discussion on natural increase is developed as a means of showing the dual value of the woman in the slave society. She was not only valuable as a source of labor but as a reproducer of future labor power. The plantocracy sought to exploit and control the slave woman’s reproductive capacity and sexuality in order to perpetuate its wealth in sugar, coffee, cotton or other staple products. Amelioration came about as the British Government’s bid to bring an end to slavery by means of a gradual process: to improve the conditions of the slaves, then to end the slave trade and finally to emancipate the slaves. The plantocracy of the British Caribbean followed these ameliorative measures out of compulsion rather than choice. Improving the conditions of female slaves was not done out of genuine concern for the slaves themselves but out of the planters’ concern to maintain and extend their wealth.

In spite of the measures taken by the plantocracy in Grenada, as in most of the colonies there was a natural decrease rather than increase. As early as 1799, this process was evident from plantation records and especially from the well-documented slave registration figures for 1817-1833. Examples could be taken from St. Patrick and St. Andrew as the largest sugar producing areas of the island. On the Madeys Estate in the Parish of St. Patrick in 1799, 6 slaves were born. However, 9 slaves died that year.

Malnutrition

Along with the rigorous work regime, poor diet, unsanitary living conditions and diseases contributed to infertility. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that there was a link between malnutrition and the irregularity or absence of ovulation. Malnutrition could also considerably delay post-partum recovery which in turn impeded the ability to become pregnant again. Evidence from a number of plantation records in Grenada and throughout the region point to the slave diet as being one of salted meat or fish, corn, flour, green banana and other provisions. In most of the colonies, planters gave slaves provision grounds on which to plant food to supplement what was imported.

The Marketplace

In 1799 a leading Grenadian planter, Alexander Campbell, observed that it was ‘the custom’ in Grenada to ‘grant slaves a piece of land as they could work, because it had been universally considered the greatest benefit to a planter that his negroes should have a sufficient quantity of provisions. On these grounds the slaves grew mainly ground provisions like yams, eddoes, cassava, sweet potatoes; tree crops like plantain, banana, breadfruit; grains; and legumes. They also reared fowls, hogs, and sheep. By the 1790s the slaves sold their excess produce at the local markets and virtually monopolized the internal market system. Alexander Campbell explained the twofold benefit of provision grounds to the slaves. Firstly, he noted, the negroes made money for themselves and the more they did so, the more attached they were to the plantation. Secondly while the planters did raise some poultry and hogs their chief consumption was bought from the slaves.

It was slave women who mainly marketed the produce of the provision grounds. Slave and free, plantation and urban women were hucksters, peddling and bartering provisions and dry goods between urban and rural areas. Planters gave evidence of how productive the provision grounds were. James Ballie, a Grenadian planter, claimed that some of the slaves possessed property worth 40, 50, 100, and even as much as 200 sterling. Such property, he explained, was regularly conveyed from one generation to another without any interference whatever. There were a number of problems related to the working of provision grounds and the sale of the produce. Planters seldom inspected provision grounds to monitor the state of cultivation or the fertility of the soil.

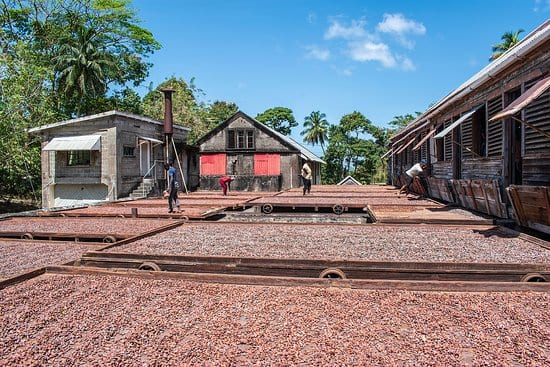

Gouyave, Dougalston Estates

The slaves had to indicate when the soil was depleted and when new grounds were needed. Provision grounds were defenseless against drought, hurricanes or theft. In the 1831 hurricane in Grenada the provision grounds of the Lataste Estate were destroyed. The slaves in desperation and hunger resorted to eating unripen provisions which made them ill and forced them to rely on rations of expensive imported grain. In response to abolitionist pressure in 1823, the British Government curtailed the Sunday market and thereby disrupted the slaves’ traditional commercial routine. It deprived them of access to large volumes of business transacted on a weekend. After 1828, hucksters in St. George’s engrossed the produce brought into town by the rural slaves on Thursday, the new official market day and then retailed it at inflated prices. While provision grounds might have provided the slave with a secure source of nutrition, not all slaves were able to cope with the labor demands of the plantation and effective cultivation of provision grounds. Thus, not all the slaves had an opportunity to enhance their standard of living.

Slaves Diet

Caribbean slave diet was a high carbohydrate, low fat one. Fresh meat was raised by some slaves, but it appears to have been sold to the white inhabitants. Evidence suggests that meat that was consumed was already in an advanced state of decay. John Terry, an overseer in Grenada, testified that he had known slaves who were driven to satisfy their hunger by eating putrid carcasses. A similar condition was reported for Barbados. The slave who reared animals might have sold some and could have kept some for himself, but what of those who did not own animals? They would have depended on protein intake from salt fish or salt beef or salt pork provided by the planter. It has been estimated by modern food standards that a herring a day contains only 19.6 grams of protein. Thus, each slave received slightly more than one pound of preserved fish per week or 56.1 pounds per year. As a result, the slaves suffered from protein deficiency diseases like kwashiorkor, diarrhea, intestinal worms, tuberculosis, measles, and whooping cough. Caribbean slave diet was also low in calcium and deficient in vitamin A and B. These deficiencies led to other diseases like dirt eating or mal d’estomac, and edema or dropsy.

Infertility

The high incidence of infertility on sugar intensive areas was further compounded by prolonged lactation, “gynecological resistance” and sexual exploitation. A combination of gynecological resistance and African tradition could be given to explain the prevalence of a prolonged lactation period among slave women. It can be argued that slave women probably exercised some choice in fertility. They developed a number of contraceptive measures, of which prolonged lactation was one. By practice of nursing their babies for a long time, while perhaps abstaining from sexual intercourse, slave women were able to reduce the birth rate in the colonies. This practice was also an African custom that continued in the Caribbean. Within some societies the women would suckle their children until they were able to walk. Three years nursing was not uncommon and during this period the husband devoted his attention to his other wives. One Jamaican planter, John Ballie, noted that few of the slave women weaned their children before they were 2 years old in spite of his offering them 2 sterling if they would wean the child in 12 months.

Mortality

Slave women might have abstained from sexual intercourse in a society where the likelihood of marriage and stable family life was slim. There were also grave dangers of maternal mortality, a strong likelihood of newborn death and little lessening of the mother’s workload during pregnancy or after birth. In Grenada in the period 1817-1833 in evidence from the Slave Registration Records one notes examples of maternal maternity. On Moliner Estate in the Parish of St. George in 1833, 40-year-old Aimee died in ‘child bed’ with the remarks ‘rupture of the womb’. On Morne Rouge state in St. George in 1817, 28-year-old Angelique died in ‘childbirth’. On the Morne Fendue Estate in the Parish of St. Patrick in 1817, 35-year-old Mary Louise died from ‘convulsions after delivery.

Abortion

Slave women almost certainly used herbal mixtures and traditional potions from their own doctors, known as obeah men and women to abort children. Some members of the plantocracy linked the practice of abortion by slaves to promiscuity. It has been claimed that in order to maintain their attractiveness to whites and improve their chances of improved status they practiced abortion. Others argued that slave women aborted as a means of resistance to the slave regime and in so doing helped thwart planter efforts at natural increase. For example, on July 5, 1801 on the Boccage Estate in St. Patrick, Celest died of an abortion. The term abortion could mean involuntary miscarriage or deliberate termination of the pregnancy, in the case of Celest the evidence does not specify.

The slave women who did conceive and had a successful pregnancy and delivery were faced with a high incidence of infant mortality. Kiple noted that slave mothers were most likely calcium deficient as they entered their first pregnancy. After multiple pregnancies with calcium levels falling each time, many slave women might have become candidates for maternal tetany. He further explained that calcium is stored up by the fetus in the bones during the last three months of intrauterine life. The amount stored can vary considerably depending on the calcium nutrition of the mother. If the amount is low the infant is in danger since the amount of calcium in breast milk is not enough to maintain skeletal growth without the contribution of the infant’s stores. The slave child that was weaned also had a high carbohydrate low protein diet. Their food consisted of cornmeal or flour porridge with little or no milk.

The main diseases that affected slave children (worms, marasmus, whooping cough, flux or diarrhea) were related to nutritional deficiencies. Dr. Castles of Grenada noted that ‘worm infestation was more common in the West Indies than in England. He attributed this ‘to their vegetable diet, great part of which is used in a crude state, particularly fruits. The unsanitary conditions of estate slave huts and surroundings also contributed to a number of diseases including worm infestation. Plantations were usually situated in relatively flat land that was poorly drained and where stagnant water attracted disease carrying mosquitoes and flies.

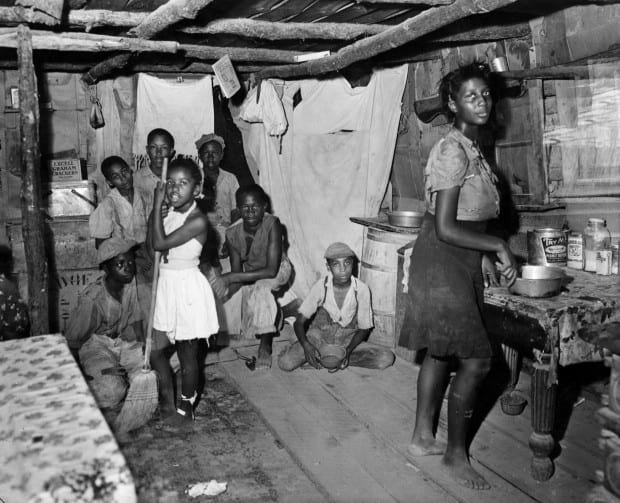

Unsanitary Conditions

There were no modern toilets; slaves would have gone ‘to the bush. Water and the soil in which slave children walked were often infested with fecal matter. Such conditions were conducive to worm infestation and gastro-intestinal diseases. From the records there is a long list of infant deaths. For example, in the Parish of St. George in 1815 on the Morne Delice Estate, Colette’s child Dorothy died at 4 months of “marasmus”. In 1833 on the Tempe Estate, St. George, Sally’s child died at 18 days old from bowel complaint and debility. In the Parish of St. Andrew 1817 on the Grand Bacolet Estate, Lizette’s child died at 5 days old of lockjaw. In 1833 on the Grand Bras Estate in the Parish of St. Andrew, Angelique’s child, Rowley, died at 20 days old from “cholic”. In the Parish of St. Patrick on the Hermitage Estate in 1817, Mary Ermine’s infant died at two months old from measles.

In the final analysis, the planter’s primary concern was to gain as much profit from his plantation as possible. If the planter sought to change the main factors that deterred natural increase such as a rigorous work regime for women, poor diet, unsanitary living and working conditions, they would have had to change the entire organization of sugar cane cultivation. This would have inevitably reduced their profits. For example, they would have had to reduce the work demands on women, improve their diet, provide better housing and proper drainage facilities. This would have meant an extensive outlay of capital and a reduction of output.

Natural Right

There is a direct connection between resistance and the concept of the human beings’ natural right to be free. The concept of natural law was put forward by European thinkers like John Locke, Voltaire and Rousseau. According to this concept, man had a natural right to be free. Such ideas of life, liberty and pursuit of happiness characterized the great Revolutions of the eighteenth-century Western world. If freedom was the natural universal condition of the human being, by logical deduction this was supposed to include men and women of all races, colors and ethnicities. It therefore follows that the black slave had a natural right to be free which was being withheld from her and him. The fact that this ‘natural right’ was being withheld from the slave meant that she or he had a ‘natural right’ to reclaim that freedom that was taken from them. The slave rebel, therefore, could be seen as a natural rebel. One must now question whether there was a gender dimension to this resistance. Did women have more reason to rebel than men? What specific forms did female rebellion take?

She’s a Rebel

The slavery system impacted upon the black woman in deeper and more profound ways than was the case with black men. At least by the mid-eighteenth-century slave women formed the backbone of the field labor force that was not only physically strenuous, but also contributed to their inability to produce healthy children. This coupled with poor living accommodation and poor health, caused the birth rate of the region to be low. Coming from an African tradition where women were seen as special and precious, this was difficult for female slaves to accept. Within the African cultural system women were often associated with high sacredness. The most vital event in a woman’s life was bearing children. This was of great importance to her and to the society. Without mother and child, the society would die out and as such they were seen as precious. Female slaves were not discriminated against in the punishment they received even when they were pregnant. They were more vulnerable to sexual abuse than men. Such atrocities propagated against them produced in them a natural propensity to resist and rebel as a basic means of survival.

Female slave resistance was notable for its diversity. Female slaves took action to weaken the slave system and to hasten its collapse. For example, malingering on estates, feigned illness, arson, and stealing, and self-inflicted mutilation. More drastic measures included running away, poisoning their masters, murder of the plantocracy, self-manumission, marronage and armed rebellion. Women also took specific action in the form of infanticide and abortion. The term used is gynecological resistance or strike. Through these means they sought to bring a speedier end to slavery.

Runaways

Most of the evidence of female resistance to slavery in Grenada relates to running away. There were numerous notices in the St. George’s Chronicle and Grenada Gazette and the Grenada Free Press and Public Gazette over the period 1815-1829 on female runaways. During the period 1808-1821, the female runaways outnumbered males. Females accounted for 62%, while men accounted for 38% of 703 runaways. On the list of runaway slaves taken by the rangers from 30 November 1828 to 31 March 1829 there were 14 women. Some of the women absented themselves from estates for long periods. For example, Mary Ursule and Sally were runaways from the Crochu Estate for 23 years and 20 years respectively. Dawphne, an African described as having marks on her face, was a runaway from the Grand Anse Estate in St. George for 14 years. From the vivid descriptions of runaways given by the planters, one can get a sense of their physical appearance, the false identities they used and the attributes they used to maintain their freedom

From the subscriber on Thursday last a negro woman named Sofy about five feet five inches high dark complexion had on when absconded an osnaburg coat and white shift, speaks English and French, she has been sent out sometimes to sell jelly pickles and preserves about the town previous to this.

Another advertisement mentioned a woman who spoke three languages, English, French, and Spanish. Others mentioned women of a yellowish complexion who passed themselves off as free. These women ingeniously used their light skin color and their knowledge of different languages to disguise their status as slaves. Runaways of both sexes might have fled to join spouses or other kin from whom they were separated. The advertisements often alleged that the runaways were being harbored by friends or kin. For example, 20-year-old Kitty was supposed to be harbored ‘in and about the neighborhood of the town or Richmond Hill or its vicinity.’ A young girl named Fancheon was allegedly harbored by friends at Grand Anse, St. George’s. Some runaways traveled quite far. Flora ran away from Gouyave and was seen in Richmond Hill, St. George, approximately fifteen miles away. Female slaves ran away while in their ‘teens’ and earlier. For example, 12-year-old Kitty ran away 6 weeks prior to April 1, 1815; and 16-year-old Mary nicknamed Monkey, ran away in September 1821. There was also evidence of runaway female slaves from the sister island of Carriacou. For example, Betsey a 22-year-old creole slave of Hope Estate absconded in November 1823. Zabat had by July 1815, absconded for 10 months. She was the property of Mary Louise St. Hillaire of Carriacou.

Some women ran away with their children, like Mary Joseph and her two infant children. Others were persistent runaways in spite of the punishment they received. For example, Therese was described as an ‘incorrigible runaway’ who received 50 lashes in 1813 and was sentenced to work in chains for 6 months and to be confined in the stocks noon and night. Etienne and Susey, after receiving 39 lashes on the public parade, ‘still persisted in refusing to return to the estate’; they were locked in for 6 months.

Suicide

Suicide was also a means of rebelling against slavery. For the slave it meant the end of a miserable life and for the planter the loss of a valuable asset. There was evidence of such rebellion in Grenada. Bella a slave on Lataste estate hanged herself in September 1809. The records described the incident as ‘an old woman who hanged herself in a fit of insanity. Bella’s age was not given. However, an old or superannuated slave would have been fifty to eighty years old. (There was evidence of Grenadian slaves as old as eighty.) While Bella’s rationale for taking her life might not be known, a few points could be made. Most superannuated slaves felt alienated, isolated and defenseless. Their services were no longer needed in the fields and most were sent to take care of children, oversee the hog meat gang or work about the house. Some managers sold them off at a low price. Others wilted away and died if they were thrown off estates. To escape such a miserable end to an already degrading life as a slave, they might have opted for suicide. Females not only reduced planter assets by taking their own lives, but also by destroying crops and equipment. In 1823, John Wells manager of Ballies Bacolet Estate in St. Andrew, noted that Eliza received 20 stripes for violent behavior in the field. On 19 February the same year, Germaine was given 15 stripes for willfully destroying canes in the field and general neglect of duty.

Economic Oppression

As mentioned earlier, slave, free black and free colored women took the lead in the internal market system in the colonies. While planters recognized their economic importance, they were worried by the entrepreneurial independence they fostered. As such, laws were passed restricting the sale of goods by slaves. The Grenada Legislature passed an Act in 1767 preventing persons from hawking and peddling goods from house to house. By this Act slaves who were found selling goods other than provisions were to be publicly whipped. The 1784 law, however, stated that the practice of permitting slaves to sell produce had been found to be productive of great mischief, by tempting then to rob their masters and neighbors. In order to prevent this, it enacted that all slaves selling sugar, rum, coffee, cocoa, cotton, molasses or indigo within six days of the publication of the Act would be punished at the discretion of the justice. In September 1829, a female slave Jane Hurst, rebelled against the above law and was convicted in the penalty of 50 sterling for selling rum in less quantity than twenty gallons. She was required to pay the fine five days later or a face possible imprisonment.

Fedon Rebellion

Grenada’s largest uprising within the period of slavery was led by Julien Fedon, a free colored planter and slave owner, in 1795. Fedon and his free colored compatriots were struggling against discrimination by the British on account of their color and French nationality, and against restrictions on their political and social rights. The free colored rebels were joined by the slaves who saw the free colored as allies in fighting against the system of slavery. According to an eyewitness, John Hay, on his way to imprisonment at Fedon’s Camp, the headquarters of the rebels, ‘we were met by numbers of negroes of both sexes.’ He further noted that a woman with whom one of the leaders of the revolt had a child was taking part in plundering his property. He noted that ‘she was very busy packing up and sending away the few articles of glass and earthenware which had yet remained without either speaking or taking the least notice of me. On Sunday 8 March 1795, he reported that at Fedon’s camp ‘a great number of men women and children joined this day and enjoyed themselves in feasting dancing and singing. However, there is no evidence from authentic sources that women were actively involved in the fighting. Hay did mention that Fedon’s wife and daughter were present at the massacre of the British prisoners. He described them as ‘unfeeling spectators’ of Fedon’s ‘horrid barbarity. There was evidence of women involved in transporting weapons, plundering provision grounds of plantations, property of planters, and taking part in the cultivation of food crops on small plantations of the leaders of the rebellion.

A number of free colored women were supposedly involved in sending supplies to Fedon’s troops. Madame Peschian and Madame Reynauds were noted in the records as two of the suppliers for the rebels. In fact at the end of the rebellion, while no women were executed, a committee was established in September 1796 by the governor to examine into the characters and conduct of the free colored women many of whom were lying under strong suspicion of having taken an active part with the insurgents and rebels during the insurrection. When, in May 1797, some female relations of the executed rebels attempted to re-enter Grenada from Trinidad, there was a public outcry against them. The outcry was so loud that Governor Charles Green accepted the Council’s advice in refusing them permission to land. An Act of 27 December 1797 listed such women whom the Committee judged improper were unable to re-enter the island.

The insurrection left extensive damage in its wake. Grand Bras Estate records noted ‘every building was destroyed, and every negro fled.’ Lataste Estate’s damages amounted to 22,652.15 sterling. Overall slave owners’ loss amounted to 2.5 million sterling. This included destruction of plantations, loss of harvests, and about 7000 dead slaves.

Conclusion

In the heyday of slavery, the British Caribbean plantocracy valued women as work units more than as breeding units. However, in the wake of the abolitionist movement within Britain and the impending closure of the slave trade, planters sought to implement ameliorative measures, in order to enhance population growth. In spite of their concerted efforts to encourage reproduction the slave population of all the sugar colonies, except Barbados, declined until Emancipation in 1834. In Grenada, a combination of factors led to a decline in the population, except in the years 1822, 1827 and 1833. These factors included poor diet, unhealthy surroundings, diseases, a severe work regime, and the non-conciliatory attitude of the planters. While on the one hand the planters sought to introduce measures to induce female slaves to reproduce, on the other hand they thwarted their own efforts. For example, it was not until 1825 that the whip was removed from the fields in Grenada. The Legislative Council objected and described women as ‘troublesome’. There were noticeable flaws in Grenada’s Guardian Act. The guardian themselves were members of the plantocracy and the upper class and thus not objective. Complaints made by slaves were merely ignored.

While it can be argued that the planters’ efforts did bear fruit, it only materialized in 1834 at Emancipation. Judging from the efforts of planters in Jamaica and Barbados, there was a long interval between the introduction of ameliorative measures and the gaining of results. Barbados implemented ameliorative measures in about 1750; increase in birth rates came in 1817. Jamaica’s implementation was about 1780 and by 1838 there were positive results. These colonies showed natural increase in case of Barbados 65 years after policy implementation and Jamaica 58 years later. Ameliorative measures in Grenada started in about 1788. By 1834, 46 years later, there were positive results. Or it could be argued that except for Barbados, the planters’ efforts might have had little impact on birth rates. Emancipation itself did have an impact. The ending of gang labor for many female slaves enhanced their fertility rate, their health and that of their children.

Some scholars have argued that ‘the plantation regime was less degrading and repressive for women. As such women were more accommodating to slavery and did not rebel as much as their male counterparts. From the evidence presented in this article, it can be ascertained that the system of slavery was just as degrading and repressive for women. She was seen as a prime worker and a breeder, a twofold responsibility that did not extend to the men. Like her male counterparts, she too had a natural right to freedom and by any means necessary she sought to attain it.

SLAVE EYES

Not again, Massa, not again

Spare me pain, man, the pain, the pain

Why? Is it because you see fire in my eyes?

The smirk in my smile?

The royalty in the way I rise?

Why? Is it because I conquer all that prevails?

You do not like my ways?

The hypocrisy in my gaze?

It’s all true, Massa, it’s all true

But please, not the whipping,

Not the flogging,

Not the pain.

But you don’t understand when I speak with my eyes,

So I might as well runaway, runaway.

References

1 Hilary Beckles Natural Rebels, p. 2.

2 Linda Roberts, St. Joseph’s Convent, St. George’s, Grenada, Jubilee 2000 Magazine. The Holy Will of God (Port of Spain: P.J. Production, 2000)

19 Comments

Upcoming Posts

Dave Chappelle Grenadian Roots

Shervone Neckles

Grand Etang Lake

Africans unite. We are one. Stop the fighting and the killing. We are brothers and sisters. WE ARE ONE!!!

I will commend the researcher and highly recommend that this piece be read by everyone.

Yes it’s worth the read although a little wordy at times but definitely informative. I would suggest a must read especially with the images attached throughout the article.

Man, this is just magnificent. Never knew about this history before I was unaware that you guys are back. Looking forward to more scholarly articles.

This is great this is the type of history to be taught in our Grenadian schools and seats of learning. I find our Grenadian young people in the main have no knowledge of their history and most do not see themself as being a product of a cruel slave trade. Leaving them lost and ignorant of their history and heritage. Lost .

I was taught a bit about the Transatlantic slave trade in my history class.

hello!,I really like your writing very a lot! proportion we

be in contact extra approximately your post on AOL? I require a specialist in this space

to unravel my problem. May be that is you! Having a look ahead to see you.

[…] SLAVERY IN GRENADA AND THE CARIBBEAN – I Am Grenada […]

https://DreamProxies.com analysis – 100 superior plus anonymous private proxies, best prices together with USA private proxies

After study a few of the weblog posts on your website now, and I actually like your means of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website listing and will probably be checking again soon. Pls take a look at my web site as nicely and let me know what you think.

Enjoyed reading through this, very good stuff, thankyou.

I will right away snatch your rss as I can not find your email subscription link or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Kindly permit me understand so that I may subscribe. Thanks.

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: iamgrenada.com/slavery-in-grenada-and-the-caribbean/ […]

I could not resist commenting. Exceptionally well written!

Hi, There’s no doubt that your site may be having internet browser compatibility problems. Whenever I take a look at your site in Safari, it looks fine however, if opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping issues. I simply wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other than that, wonderful blog!

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 78596 more Info on that Topic: iamgrenada.com/slavery-in-grenada-and-the-caribbean/ […]

You made some good points there. I checked on the net to find out more about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this site.

I truly love your website.. Excellent colors & theme. Did you make this site yourself? Please reply back as I’m trying to create my very own blog and would love to learn where you got this from or just what the theme is called. Appreciate it!

Can I just say what a relief to find someone who really understands what they’re discussing online. You certainly know how to bring a problem to light and make it important. More and more people really need to check this out and understand this side of the story. I was surprised that you aren’t more popular since you definitely possess the gift.