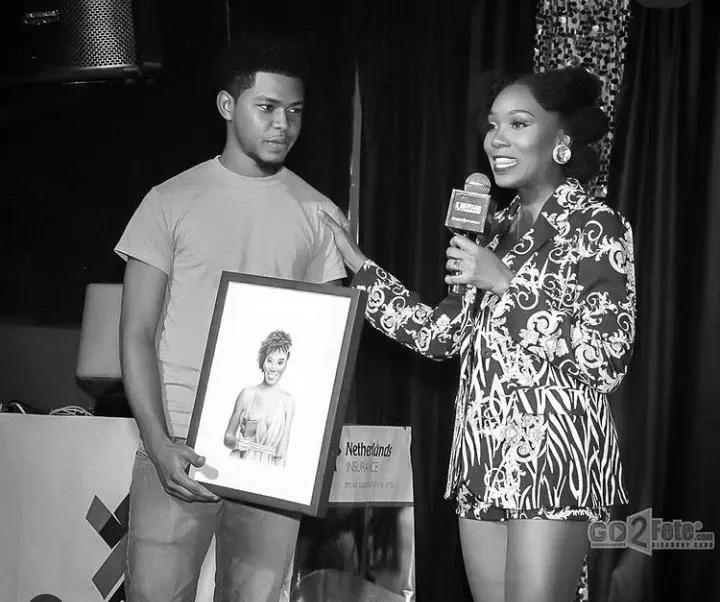

Superstar R&B Artist Official Angello

Allister Amada Spoken Word Contest Winner

Winner

Lilian Langaigne contest winner

Jenson Mitchell aka Highroof Spirit Lead Spoken Word Piece

Ellington Nathan Purcell aka “Ello”

A must watch Spoken Word

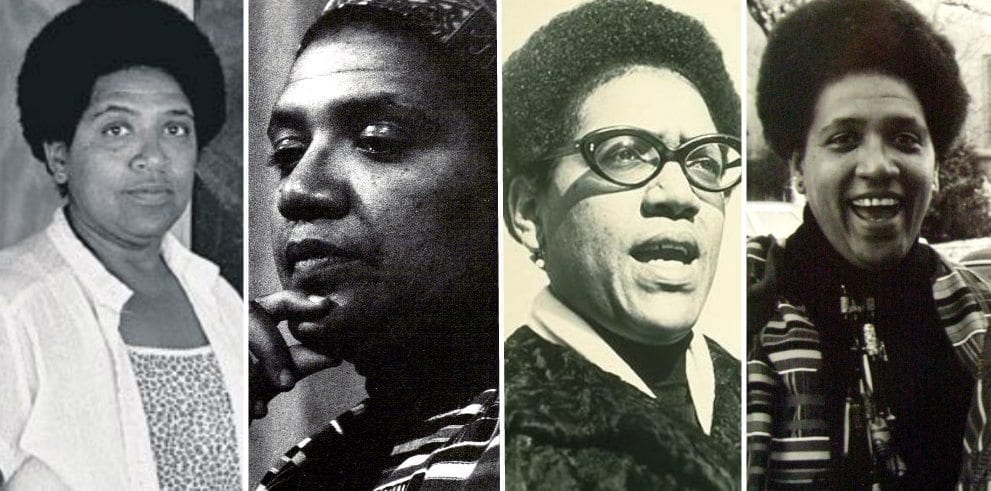

Audre Lord was born Audrey Geraldine Lorde on February 18, 1934. She was an American writer, feminist, womanist, librarian, and civil rights activist. She was a self-described “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” who dedicated both her life and her creative talent to confronting and addressing injustices of racism, sexism, classism, hetero-sexism, and homophobia.

As a poet, she is best known for technical mastery and emotional expression, as well as her poems that express anger and outrage at civil and social injustices she observed throughout her life. Her poems and prose largely deal with issues related to civil rights, feminism, lesbianism, illness, disability, and the exploration of Black female identity.

Early life

Lorde was born in New York City to Caribbean immigrants. Her father Frederick Byron Lorde was from Barbados and her mother Linda Gertrude Belmar Lorde was a Grenadian from the island of Carriacou, who settled in Harlem in New York City. Lorde’s mother was of mixed ancestry but could “pass” for ‘Spanish’, which was a source of pride for her family. Lorde’s father was darker than the Belmar family liked, and they only allowed the couple to marry because of Byron Lorde’s charm, ambition, and persistence.Lorde was nearsighted to the point of being legally blind and the youngest of three daughters (her two older sisters were named Phyllis and Helen), Lorde grew up hearing her mother’s stories about the Caribbean especially about her little island Carriacou. At the age of four, she learned to talk while she learned to read, and her mother taught her to write at around the same time. She wrote her first poem when she was in eighth grade.

Born as Audrey Geraldine Lorde, she chose to drop the “y” from her first name while still a child, explaining in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name that she was more interested in the artistic symmetry of the “e”-endings in the two side-by-side names “Audre Lorde” than in spelling her name the way her parents had intended.

Lorde’s relationship with her parents was difficult from a young age. She spent very little time with her father and mother, who were both busy maintaining their real estate business in the tumultuous economy after the Great Depression. When she did see them, they were often cold or emotionally distant. In particular, Lorde’s relationship with her mother, who was deeply suspicious of people with darker skin than hers (which Lorde’s was) and the outside world in general, was characterized by “tough love” and strict adherence to family rules. Lorde’s difficult relationship with her mother figured prominently in her later poems, such as Coal’s “Story Books on a Kitchen Table“.

As a child, Lorde struggled with communication, and came to appreciate the power of poetry as a form of expression. In fact, she describes herself as thinking in poetry. She also memorized a great deal of poetry, and would use it to communicate, to the extent that, if asked how she was feeling, Audre would reply by reciting a poem. Around the age of twelve, she began writing her own poetry and connecting with others at her school who were considered “outcasts”, as she felt she was.

She attended Hunter College High School, a secondary school for intellectually gifted students, and graduated in 1951. While attending Hunter, Lorde published her first poem in “Seventeen” magazines after her school’s literary journal rejected it for being inappropriate. Also, in high school, Lorde participated in poetry workshops sponsored by the Harlem Writers Guild but noted that she always felt like somewhat of an outcast from the Guild. She felt she was not accepted because she “was both crazy and queer but [they thought] I would grow out of it all.”

Career

Audre Lorde in 1954, spent a pivotal year as a student at the National University of Mexico, a period she described as a time of affirmation and renewal. During this time, she confirmed her identity on personal and artistic levels as both a lesbian and a poet. On her return to New York, Lorde attended Hunter College, and graduated in the class of 1959. While there, she worked as a librarian, continued writing, and became an active participant in the gay culture of Greenwich Village. She furthered her education at Columbia University, earning a master’s degree in library science in 1961. During this period, she worked as a public librarian in nearby Mount Vernon, New York.

In 1968 Lorde was writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi. Lorde’s time at Tougaloo College, like her year at the National University of Mexico, was a formative experience for her as an artist. She led workshops with her young, Black undergraduate students, many of whom were eager to discuss the civil rights issues of that time. Through her interactions with her students, she reaffirmed her desire not only to live out her “crazy and queer” identity, but also to devote attention to the formal aspects of her craft as a poet. Her book of poems, Cables to Rage, came out of her time and experiences at Tougaloo.

From 1972 to 1987, Lorde resided on Staten Island in NY. During that time, in addition to writing and teaching she co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press.

In 1977, Lorde became an associate of the Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press (WIFP). WIFP is an American nonprofit publishing organization. The organization works to increase communication between women and connect the public with forms of women-based media.

Lorde taught in the Education Department at Lehman College from 1969 to 1970, then as a professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (part of the City University of New York, CUNY) from 1970 to 1981. There, she fought for the creation of a Black studies department. In 1981, she went on to teach at her alma mater, Hunter College (also CUNY), as the distinguished Thomas Hunter chair.

In 1980, together with Barbara Smith and Cherríe Moraga, she co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the first U.S. publisher for women of color. Lorde was State Poet of New York from 1991 to 1992.

In 1981, Lorde was among the founders of the Women’s Coalition of St. Croix, an organization dedicated to assisting women who have survived sexual abuse and intimate partner violence. In the late 1980s, she also helped establish Sisterhood in Support of Sisters (SISA) in South Africa to benefit Black women who were affected by apartheid and other forms of injustice.

In 1985, Audre Lorde was a part of a delegation of Black women writers who had been invited to Cuba. The trip was sponsored by The Black Scholar and the Union of Cuban Writers. She embraced the shared sisterhood as Black women writers. They visited Cuban poets Nancy Morejon and Nicolas Guillen. They discussed whether the Cuban revolution had truly changed racism and the status of lesbians and gays there.

Films

Lorde had several films that highlighted her journey as an activist in the 1980s and 1990s.

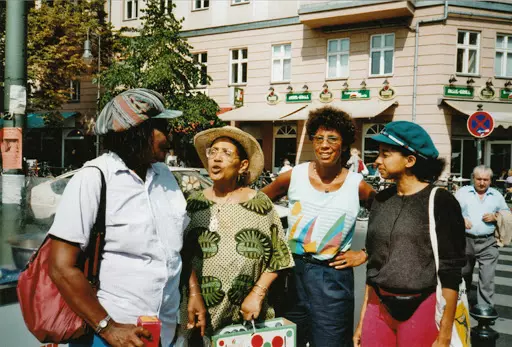

The Berlin Years: 1984–1992 documented Lorde’s time in Germany as she led Afro-Germans in a movement that would allow Black people to establish identities for themselves outside of stereotypes and discrimination. After a long history of systemic racism in Germany, Lorde introduced a new sense of empowerment for minorities. As seen in the film, she walks through the streets with pride despite stares and words of discouragement. Including moments like these in a documentary was important for people to see during that time. It inspired them to take charge of their identities and discover who they are outside of the labels put on them by society. The film also educates people on the history of racism in Germany. This enables viewers to understand how Germany reached this point in history and how the society developed. Through her promotion of the study of history and her example of taking her experiences in her stride, she influenced people of many different backgrounds.

The film documents Lorde’s efforts to empower and encourage women to start the Afro-German movement. What began as a few friends meeting in a friend’s home to get to know other Black people, turned into what is now known as the Afro-German movement. Lorde inspired Black women to refute the designation of “Mulatto”, a label which was imposed on them, and switch to the newly coined, self-given “Afro-German”, a term that conveyed a sense of pride. Lorde inspired Afro German women to create a community of like-minded people. Some Afro-German women, such as Ika Hugel-Marshall, had never met another Black person and the meetings offered opportunities to express thoughts and feelings.

Personal identity

Throughout Lorde’s career she included the idea of a collective identity in many of her poems and books. She did not just identify with one category, but she wanted to celebrate all parts of herself equally.

She was known to describe herself as Black, lesbian, feminist, poet, mother, etc. In her novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, Lorde focuses on how her many different identities shape her life and the different experiences she has because of them. She shows us that personal identity is found within the connections between seemingly different parts of one’s life, based in lived experience, and that one’s authority to speak comes from this lived experience. Personal identity is often associated with the visual aspect of a person, but as Lies Xhonneux theorizes when identity is singled down to just to what you see, some people, even within minority groups, can become invisible.

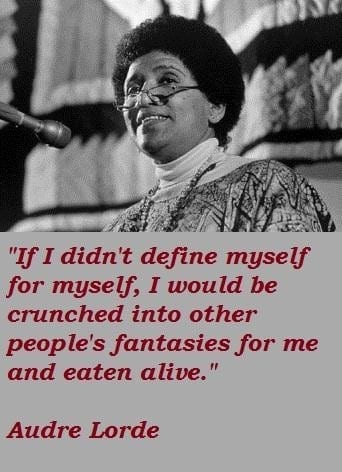

In, The Cancer Journals she wrote “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.” This is important because an identity is more than just what people see or think of a person, it is something that must be defined by the individual. “The House of Difference” is a phrase that has stuck with Lorde’s identity theories. Her idea was that everyone is different from each other and it is the collective differences that make us who we are, instead of one little thing. Focusing on all of the aspects of identity brings people together more than choosing one piece of an identity.

Lorde’s works “Coal” and “The Black Unicorn” are two examples of poetry that encapsulates her Black, feminist identity. Each poem, including those included in the book of published poems focus on the idea of identity, and how identity itself is not straightforward. Many Literary critics assumed that “Coal” was Lorde’s way of shaping race in terms of coal and diamonds. Lorde herself stated that those interpretations were incorrect because identity was not so simply defined, and her poems were not to be oversimplified.

While highlighting Lorde’s intersectional points through a lens that focuses on race, gender, socioeconomic status/class and so on, we must also embrace one of her salient identities; Lorde was not afraid to assert her differences, such as skin color and sexual orientation, but used her own identity against toxic Black male masculinity. Lorde used those identities within her work and used her own life to teach others the importance of being different. She was not ashamed to claim her identity and used it to her own creative advantages.

While highlighting Lorde’s intersectional points through a lens that focuses on race, gender, socioeconomic status/class and so on, we must also embrace one of her salient identities, lesbianism. She was a lesbian and navigated spaces interlocking her womanhood, gayness and Blackness in ways that trumped white feminism, predominantly white gay spaces and toxic Black male masculinity. Lorde used those identities within her work and ultimately it guided her to create pieces that embodied lesbianism in a light that educated people of many social classes and identities on the issues Black lesbian women face in society.

Audre, Gloria, May, Ika Winterfeldmarkt

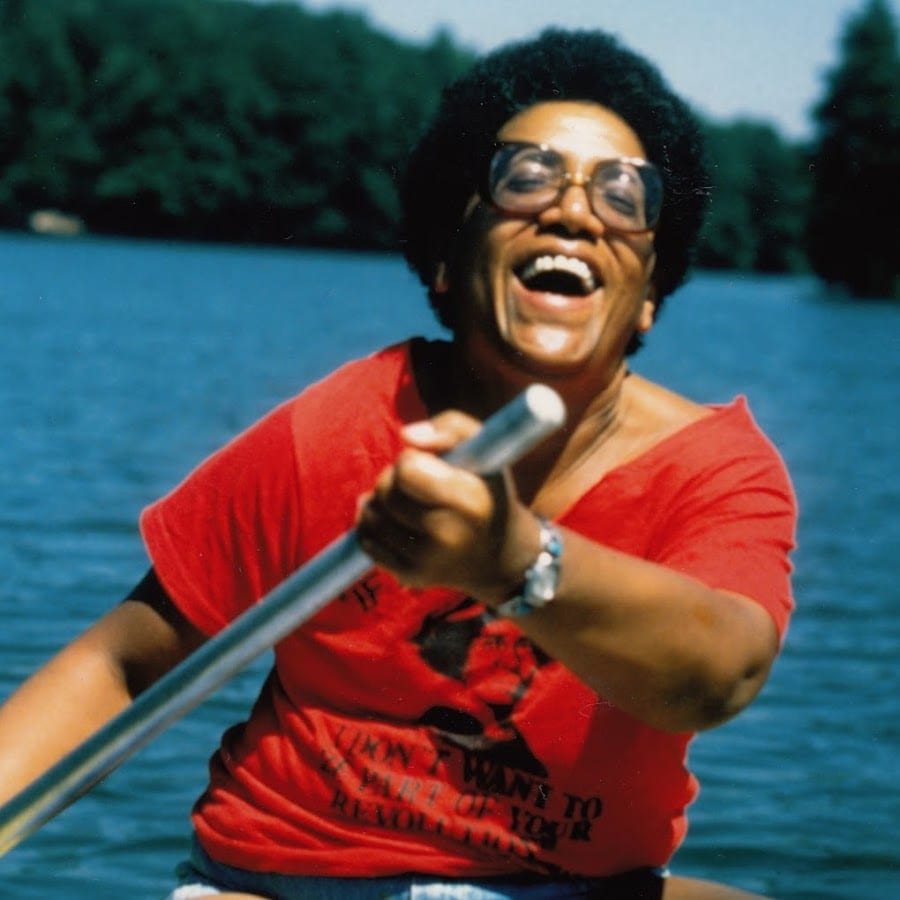

Audre im Boot Krumme Lanke

Personal life

In 1962, Lorde married attorney Edwin Rollins, who was a white, gay man. She and Rollins divorced in 1970 after having two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan. In 1966, Lorde became head librarian at Town School Library in New York City, where she remained until 1968.

From 1977 to 1978, Lorde had a brief affair with the sculptor and painter Mildred Thompson. The two met in Nigeria in 1977 at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77). Their affair ran its course during the time that Thompson lived in Washington, D.C.

During her time in Mississippi in 1968, she met Frances Clayton, a white lesbian and professor of psychology who was to be her romantic partner until 1989. Their relationship continued for the remainder of Lorde’s life.

Lorde and her life partner, Black feminist Dr. Gloria I. Joseph, resided together on Joseph’s native land of St. Croix. Together they founded several organizations such as the Che Lumumba School for Truth, Women’s Coalition of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, Sisterhood in Support of Sisters in South Africa, and Doc Loc Apiary.

Last years

Lorde was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and underwent a mastectomy. Six years later, she found out her breast cancer had metastasized in her liver. After her first diagnosis, she wrote The Cancer Journals, which won the American Library Association Gay Caucus Book of the Year Award in 1981. She was featured as the subject of a documentary called A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, which shows her as an author, poet, human rights activist, feminist, lesbian, a teacher, a survivor, and a crusader against bigotry. She is quoted as saying: “What I leave behind has a life of its own. I’ve said this about poetry; I’ve said it about children. Well, in a sense I’m saying it about the very artifact of who I have been.”

From 1991 until her death, she was the New York State Poet laureate. When designating her as such, then-governor Mario Cuomo said of Lorde, “Her imagination is charged by a sharp sense of racial injustice and cruelty, of sexual prejudice…She cries out against it as the voice of indignant humanity. Audre Lorde is the voice of the eloquent outsider who speaks in a language that can reach and touch people everywhere.” In 1992, she received the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement from Publishing Triangle. In 2001, Publishing Triangle instituted the Audre Lorde Award to honor works of lesbian poetry.

Lorde died of breast cancer at the age of 58 on November 17, 1992, in St. Croix, where she had been living with Gloria I. Joseph. In an African naming ceremony before her death, she took the name Gamba Adisa, which means “Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known”.

(See more videos of Audre in our Gallery on our website.)

References

· “Audre Lorde Biography – eNotes.com”. eNotes.

· · Foundation, Poetry (March 3, 2020). “Audre Lorde”. Poetry Foundation. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

· “Audre Lorde”. Poetry Foundation. March 17, 2018. Retrieved

5 Comments

Upcoming Posts

Dave Chappelle Grenadian Roots

Shervone Neckles

Grand Etang Lake

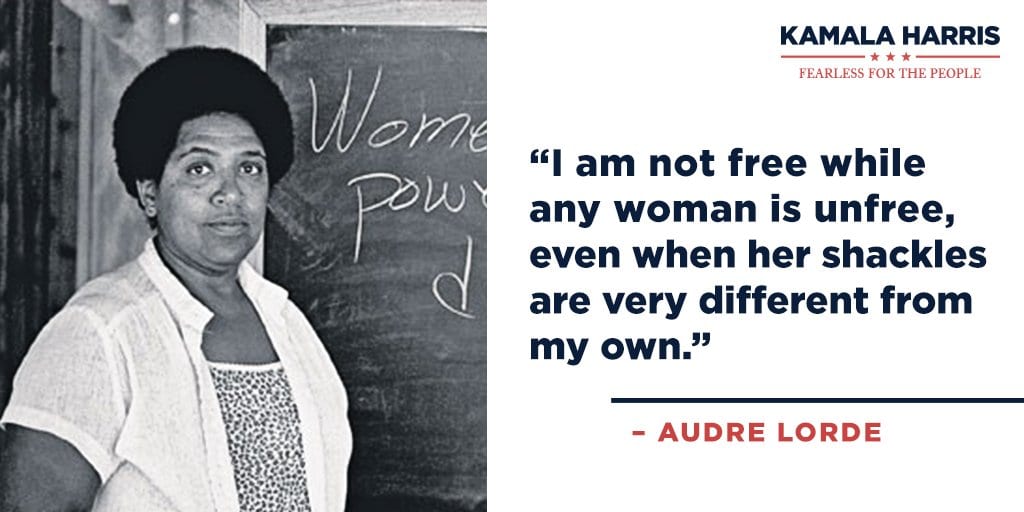

We are very proud to feature Audre Lorde on our website. Some members in our audience might have a different opinion but we chose to celebrate her accomplishments. In the era that she lived, she was a Trail Blazer, a Game Changer, a Grenadian who continues to Make Waves.

Grenada has and keep producing citizens that are making positive impact in our world and we here at I Am Grenada will continue to showcase and promote our citizens regardless of the negative opinion of those in the minority.

Our world is changing, we all must choose to evolve and always eager to learn and adapt without changing our core Godly Principles and Values. We cannot be stagnant in life.

Kudos to Audre Lorde!!!!!!!

Ok

This is a Game Changer. Audre was awesome even though I personally disagree with her lifestyle. She did something that most of us wouldn’t dare do. I know that I wouldn’t but I applaud her with her conviction. She was an educator, Lesbian Black Lady who was way ahead of her time. Why is it that I never heard about her before? Where do you get them from?

I am an American and very proud of Audre. I am also a Christian and know about the Love and Grace of God. We don’t have to condone any activity that’s contrary to our beliefs but we are called to Love. Hoping that she gave her life to Christ prior to her death. Audre was an amazing character who stood for what she believed in. Most people I know of are afraid to make a stand.

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: iamgrenada.com/audre-lorde-carriacou/ […]