Superstar R&B Artist Official Angello

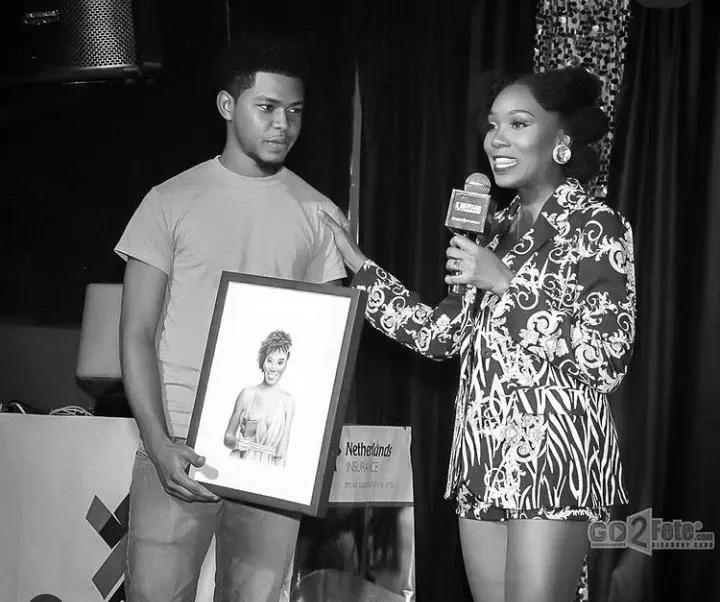

Allister Amada Spoken Word Contest Winner

Winner

Lilian Langaigne contest winner

Jenson Mitchell aka Highroof Spirit Lead Spoken Word Piece

Ellington Nathan Purcell aka “Ello”

A must watch Spoken Word

Did You Know

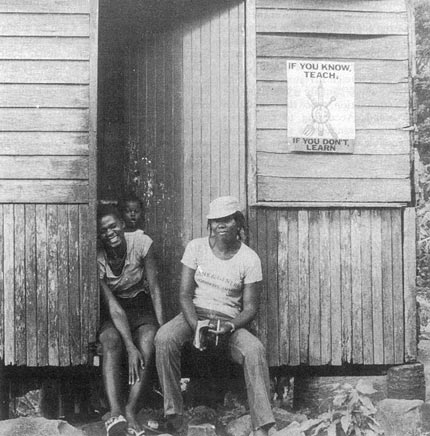

Grenada, like many of the Caribbean islands, is subject to a large amount of out-migration, with a large number of young people seeking more prospects abroad? Popular migration points for Grenadians included more prosperous islands/countries in the Caribbean such as, Panama, Venezuela, Trinidad, The British Virgin Islands, Aruba, Barbados. North American Cities such as New York City, Toronto, and Montreal. The United Kingdom in particular, London, Yorkshire and Australia.

Grenadians first migrated to Trinidad in the early 19th century. There were approximately 50,000 Grenadian-born living in the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago especially in the Point Fortin district, where about 5,000 lived. Trinidad and Tobago has been one of the most prosperous countries in the Caribbean, primarily due to significant oil and natural gas resources, high levels of direct foreign investment and an expanding tourist industry. The “pull” factor was therefore strong. Available data suggest that one-third of intra-Caribbean migrants resided in Trinidad and Tobago.

Little is known about the history of Trinidad and Tobago prior to the recorded arrival of Christopher Columbus on their shores in 1498. By the 1300s, the island was largely populated by Arawak and Carib populations, of which little physical trace remains. These populations were largely wiped out under the Spanish encomienda system, which pressured the natives to convert to Christianity and labor as slaves on Spanish Mission lands in exchange for “protection”. By 1700 Trinidad, a sparsely populated jungle-island, belonged to the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which at that time comprised Mexico, Central America, and the southwestern United States. In an effort to populate the island, King Carlos III issued the 1783 Cedula de Poblacion that granted free lands to any foreign settlers and their slaves in exchange for a sworn allegiance to the Spanish crown. As a result, numerous Martinique Creole planters settled in Trinidad. It would be these French planters, and other Europeans attracted by the promise of free land that developed Trinidad’s extremely profitable sugarcane and cocoa industries.

Trinidad was part of the Spanish Empire until 1796, when Sir Ralph Abercromby and his 18 warships surrounded the island, forcing the Spanish Governor Don Jose Maria Chacon to surrender the island to British forces. By 1802, the territory was ceded to the British Crown whereby it became an official colonial subsidiary. Trinidad’s sugar industry, which English investors were keen to expand, proved extraordinarily profitable. African slaves, forcibly brought to the island in the 17th century, constituted the majority of the labor force on the island’s sugar and cocoa plantations. With an 1838 Act of Parliament abolishing slavery in all British territories, Trinidad’s agricultural economy teetered on the verge of collapse; newly freed Africans refused to work any further on the plantations and left the fields en masse.

To prevent complete disintegration of the sugar and chocolate industries, experiments with new sources of labor began. Chinese, Portuguese, African-Americans, and, most notably, Indians were shipped to Trinidad as indentured laborers to revive the island’s anemic economy. These new populations were to irrevocably alter the cultural phylogeny of the island. Indians proved the most resilient and ready workers; one early report describes Indians as “valuable steady laborers”. They were consequently recruited in greater numbers than those from any other country, and by 1891, the island’s Indian population was already above 45,800. From 1845 to 1917 there was continuous migration to Trinidad until the Indian Legislative Assembly abolished the system of indentureship.

During the mid-1950s, when the Trinidadian oil refineries were mechanized and downsized operationally, a group of Grenadian oil workers were allowed entrance into the United States as immigrants. According to Paula Aymer, “these restless men and women were determined to find their way into the United States, and they used various means. Some had made important job connections while working in the oil enclave or on the naval base (at Chaguaramas, Trinidad) and had been given references by American employers. Others had sent their children to [U.S.] schools, and once these children found jobs and sponsors to help them with the immigration requirements, they applied for permanent residence for their parents. Still others first found work on oil refineries in the United States Virgin Islands, or traveled first to England, and from there found their way, often via Canada, into the United States.”

Canadians reported to have Caribbean origins in the 2016 census. The vast majority immigrated to Canada after the multiculturalism policy was initiated in 1971 by then prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau. The first phase was between 1900 to 1960. During this period, Canada accepted about 21,500 immigrants from Caribbean countries. The slight increase in immigration from 1945 to 1960 corresponded with postwar economic expansion and the West Indian Domestic Scheme (1955-1967) which was established, almost exclusively, for the immigration of women from Jamaica and Barbados who immigrated as domestic workers. Women like Jean Augustine from Grenada, the first Black female MP and Cabinet minister, entered Canada through this scheme.

Between 1996 and 2001, the Canadian population grew by four per cent, whereas the population of Caribbean Canadians grew more quickly and rose by 11 per cent. Most Caribbean Canadians live in the more populous provinces of Ontario and Quebec and in major urban city hubs such as Toronto and Montreal. The majority of Caribbean immigrants to Canada speak at least one of Canada’s official languages. People from Antigua, Grenada, Bahamas, Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Montserrat, St Lucia, Virgin Islands, St Kitts-Nevis, Dominica, and St Vincent generally speak English.

Canadian-sponsored live-in maid programs for people of the Caribbean enabled a few hundred Grenadian women to enter the United States as immigrants. These women settled in parts of Washington, D.C., New York, and Boston after serving the mandatory two-year requirement of the Canadian program. During the 1960s the United States developed its own program that sponsored domestic workers from the Caribbean. Hundreds of Grenadian woman entered the United States as live-in domestics in the northeastern section of the country, particularly in the New York area.

Grenadians on a whole began immigrating to the United States after the turn of the twentieth century. They settled in urban areas of the northeastern United States, by “apprenticing on [U.S.] boats that transported bananas from Central America via Barbados and jumping ship once they docked in New York or Boston.” The number of Grenadians coming to the United States in this manner amounted only to a few hundred.

According to statistics of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, in the period between 1960 and 1980 a total of 10,391 Grenadians entered the United States legally. Between 1971 and 1984 just over 12,000 Grenadian immigrants entered New York. Since 1984, according to American Immigrant Cultures, approximately 850 Grenadians have legally entered the United States each year. Again, the number of Grenadians allowed to enter the United States was very low, by comparison to European immigrants entering the United States, but greater than the number allowed earlier in the century.

Grenadians moved to the United States for a number of reasons, ranging from better economic conditions in the United States to a desire to live with relatives who immigrated to America earlier. While living in the United States, many Grenadians maintain contact with family members still residing on the island. A large number of Grenadian Americans visit relatives on the island constantly and islanders fly to the United States to visit relatives living on the continent. Some of these visitors from the island use their visit as a means of illegal entry into the United States. These persons find jobs in the United States or attend schools in the United States and do not return home to Grenada.

As Grenadians moved to the United States, older immigrants continued to maintain many traditional Grenadian customs and values, while younger Grenadian Americans began taking on more traditional American customs and values, in particular those of African Americans. Even though this change in values was occurring, contact with and support for Grenadians on the island remained high. Many organizations have been set up by Grenadian Americans in the United States whose main objective is to send monies for support back to the Island.

Upcoming Posts

Dave Chappelle Grenadian Roots

Shervone Neckles

Grand Etang Lake